“Einstein’s Monsters” is a collection of short stories and essays by the distinguished British author, Martin Amis (“Money”, “The Rachel Papers”). The book formed the basis for a radio drama project I developed in the early 90s for NPR, titled “Radio Einstein”. On this day, marking another year removed from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, this essay is a reflection on his book, and how the nuclear issue hovers, ever-present, in our individual and collective consciousness (or maybe that should be un-consciousness, given how comparatively blasé people have become on the subject). You can listen to the audio sampler from the radio series here, or click on the embedded link at the end of this post.

“I was born on August 25, 1949: four days later, the Russians successfully tested their first atom bomb, and deterrence was in place. So I had those four carefree days, which is more than my juniors ever had. I didn’t really make the most of them. I spent half the time under a bubble. Even as things stood, I was born in an acute state of shock. My mother says I looked like Orson Welles in a black rage. By the fourth day I had recovered, but the world had taken a turn for the worse. It was a nuclear world. To tell you the truth, I didn’t feel very well at all. I was terribly sleepy and feverish. I kept throwing up. I was given to fits of uncontrollable weeping….. When I was eleven or twelve the television started showing target maps of South East England: the outer bands of the home counties, the bull’s eye of London. I used to leave the room as quickly as I could. I didn’t know why nuclear weapons were in my life or who had put them there. I didn’t know what to do about them. I didn’t want to think about them. They made me feel sick.”

This is how the great British novelist Martin Amis begins his essay, “Thinkability”, which leads off his book, Einstein’s Monsters.

The short stories which follow are his attempt to find ways to write about nuclear weapons: what they embody, and what they do to us – physically, psychologically, sociologically, and all the other “-ally’s”. The stories are metaphors, allegories, psychodramas, fantasies embedded in a paradox. The paradox at the heart of the nuclear equation. Nuclear fusion and fission are derived from the primal energy of creation, yet they also give rise to such monumental destructive energy that they can end all creation. The life force is also the death force. As Amis acknowledges:

“Although we don’t know what to do about nuclear weapons, or how to live with nuclear weapons, we are slowly learning how to write about them. Questions of decorum present themselves with a force not found elsewhere. It is the highest subject and it is the lowest subject. It is disgraceful, and exalted. Everywhere you look there is great irony: tragic irony, even the irony of black comedy or farce; and there is irony that is simply violent, unprecedentedly violent. The mushroom cloud above Hiroshima was a beautiful spectacle, even though it owed its color to a kiloton of human blood.”

The “irony of black comedy or farce”, as Amis describes it, is what drives the most famous exploration of the nuclear nightmare in popular culture, Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Originally, Kubrick had intended a more-or-less straight dramatization of the series of events in his film that lead to nuclear Armageddon. But, as he worked on the project, he came to realize that the darkness of his subject could only be adequately captured with the heightened irony and absurdist tone that characterize the finished movie. One of the film’s most famous lines perfectly captures the surrealistic absurdities that lie at the heart of any contemplation of nuclear issues, whether in fact or fiction. President Merkin Muffley (Peter Sellers) admonishes General “Buck” Turgidson (George C. Scott) as he wrestles with the Soviet Ambassador on the floor of the U.S. Operations Control Room: “Gentleman! You can’t fight in here! This is the War Room.”

The film originally ended with a massive custard pie fight, a lovely allusion to the movies’ silent era, and an apt reductio ad absurdum of the nuclear stand-off.

But Kubrick felt this farcical conclusion was perhaps a little too much, diluting the point he was trying to make — and he was right.

It would have trivialized a scenario that, for all its absurdity, was deadly serious, because underneath all the antic posturing, the possibility of an accidental first strike by America’s nuclear bombers was entirely possible. So Kubrick opted for a more sobering, albeit still surreal, conclusion. The maniacal, crippled Dr. Strangelove (Peter Sellers), knowing that a Doomsday Device of planet-wide annihilation has been triggered by America’s single wayward bomber, is so transported by his visions of mass copulation amongst the survivors (with multiple female partners allocated to each man) that he rises, prophet-like, out of his wheelchair, declaring “Mein Fuhrer! I can walk!” Cut to epic, beautiful shots of nuclear orgasm derived from documentary footage of H-bomb tests, with Vera Lynn crooning on the soundtrack the old wartime standard: “We’ll meet again / Don’t know where, don’t know when / But I know we’ll meet again, some sunny day…..”

Mankind (and let me emphasize the man part of that word – I suspect womankind, left in charge, would not pursue self-annihilation with such single-minded fervor) has always seemed to find something compulsively beautiful in the rictus of death. Why else would we have continued to celebrate obliteration so fervently in our literature and art? From the earliest myths which correlate love and passion with death (Tristan and Isolde anyone?) we have now moved, inexorably it seems, to the ubiquitous fetishizing of erupting death wounds, dismemberment, and other baroque, slow-motion tours de force to be found even in your average Summer PG-13 blockbuster. And this is not to mention the lingering shots of mutilation and the casual sadism we welcome into our homes without a blink on assorted TV procedurals and Game of Thrones. As a species we are as much in love with the look of violence and death as we are with the idea of it, let alone the practice of it.

Nowhere is this dichotomy between the beauty and horror of death presented more vividly, on a more epic scale, than in the biblical splendor of the atomic detonation, and the smoldering, shimmering afterglow of the rising mushroom cloud. Take a look at the carefully restored footage of America’s nuclear testing program of 30-plus years, gathered together in the documentary Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie, and you’ll want to pop your corn and settle in for an evening of nuclear ‘shrooms. Viewing real footage of assorted atom and hydrogen bombs is beautiful, compelling, exotic and terrifying in ways that the slow-motion carnage and mayhem of the Matrix movies can only dream of being. Because this stuff is real, man! During the height of America’s above-ground testing program, families would traipse out into the desert with their picnics to watch the spectacle: a nuclear al fresco, if you will. Little did they know they were also investing in a future of mutant tumors, rebellious immune systems, and sometimes a slow-motion, radiation-soaked death incurred from drifting fallout (see the extraordinary book and website American Ground Zero).

When the scientists of the Manhattan Project witnessed the first atomic test in the Nevada desert, named in suitably Biblical fashion as Trinity, the beatific horror of what they had created, God-like, out of the building-blocks of creation rendered them, first, mute, and second, inclined towards prose tinged with a strain of scriptural poesy.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, chief architect of the Bomb, himself quoted Hindu scripture: “Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds”.

But, beneath all the hand-wringing and subsequent calls to disarm from some of the nuclear scientists, you can still sense the little boys within the fathers of Armageddon jumping for joy: “We did it!” they cry. As the cloud from Trinity arose from the desert sands, one of the scientists pronounced, more ominously, “Now we’re all sons of bitches”

In the months and years that followed the test, and the two subsequent atomic conflagrations in Japan, some of the Manhattan Project scientists, like Oppenheimer, began to more fully realize the ramifications of what they had wrought. They tried to jump off the nuclear band wagon as it picked up speed, to move the government towards disarmament. Miscalculating his political influence, Oppenheimer lived to see his security clearance revoked after a series of humiliating hearings in which he was accused of passing secrets to the Soviets. He never recovered, neither from the betrayals, nor the sense of his own culpability in bringing mankind one large step closer to its own doom, and died a broken man. Others in the scientific community, like Edward Teller (who testified against his old friend and colleague at those hearings), invested themselves heart and soul in the Faustian nuclear bargain.

Teller, more than anyone, set the US on the road to creating and stockpiling ever increasing megatons of mass-destruction. Motivated by his early experiences as a refugee from Nazi oppression before the war, he was more inclined to view the Soviets as the new Reich. For Teller and his political allies, the threat of force had to be contained by the threat of greater force, and thus the policy of Mutually Assured Destruction, or MAD, was born. Besides, the boys were hardly going to throw their shiny new toys out of the sandpit. They wanted to play, and play they did. Thus was also born this country’s epic program of nuclear tests that effectively irradiated the entire US with fallout over the course of decades. There were some in the medical community who raised alarms about the long-term effects this exposure would have on the population; their warnings (and careers) were duly curtailed by officialdom.

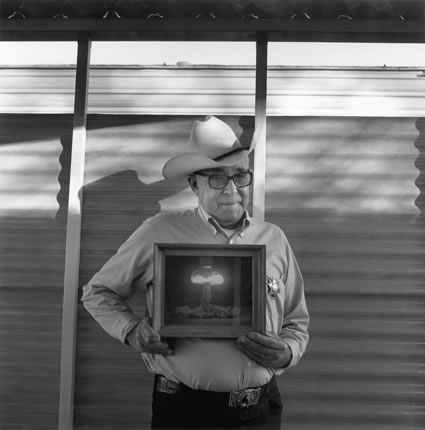

Photos taken from “American Ground Zero” by Carole Gallagher:

Teller himself remains a compelling, maddeningly enigmatic figure at the centre of the nuclear narrative. He was brilliant, zealous, paranoid, neurotic, messianic in his zeal for nuclear superiority, and, thereafter, for the so-called Star Wars missile defense shield; after giving birth to his babies, he then proceeded, Zeus-like, to find the most outré manner in which to eat them. If ever someone in real life embodied the flaws of a tragic figure like Lear or Oedipus it was Teller: tragic for himself, and for us.

In his essay “Thinkability” from Einstein’s Monsters, Martin Amis cannily zeros in on the strain of infantilism at play on the stage of the nuclear arms race:

“Trinity, the first bomb (nicknamed the Gadget) was winched up into position on a contraption known as “the cradle”; during the countdown the Los Alamos radio station broadcast a lullaby, Tchaikovsky’s “Serenade for Strings”; scientists speculated whether the gadget was going to be a “girl” (i.e., a dud) or a “boy” (i.e., a device that might obliterate New Mexico). The Hiroshima bomb was called Little Boy.

“It’s a boy!” pronounced Edward Teller, the “father” of the H-bomb, when “Mike” (“my baby”) was detonated over Bikini Atoll in 1952…. It is ironic, because they are the little boys; we are the little boys. And the irony has since redoubled. By threatening extinction, the ultimate antipersonnel device is in essence an anti-baby device. One is not referring here to the babies who will die but to the babies who will never be born, those that are queuing up in spectral relays until the end of time.”

Extending his observation of this strain of infantilism that suffuses nuclear history, Amis extrapolates a keen metaphor with which to conclude his essay. Remember this was written in 1987, before the fall of the Soviet Union; though in reality little has actually changed in terms of the political chess game (or should that be crap shoot?) which keeps us perpetually betting the house on a round of nuclear Sudden Death.

“At the multiracial children’s tea party the guest have, perhaps, behaved slightly better since the Keepers were introduced. Little Ivan has stopped pulling Fetnab’s hair, though he is still kicking her leg under the table. Bobby has returned the slice of cake that rightfully belonged to tiny Conchita, though he has his eye on that sandwich and will probably make a lunge for it sooner of later. Out on the lawn the Keepers maintain a kind of order, but standards of behavior are pretty well as troglodytic as they ever were. At best the children seem strangely subdued or off-color. Although they are aware of the Keepers, they don’t want to look at them, they don’t want to catch their eye. They don’t want to think about them. For the Keepers are a thousand feet tall, and covered in gelignite and razor blades, toting flamethrowers and machine guns, cleavers and skewers, and fizzing with rabies, anthrax, plague.

“Curiously enough, they are not looking at the children at all. With bleeding hellhound eyes, mouthing foul threats and shaking their fists, they are looking at each other. They want to take on someone their own size…..

“If only they knew it – no, if only they believed it – the children could simply ask the Keepers to leave. But it doesn’t seem possible, does it? It seems – it seems unthinkable. A silence starts to fall across the lawn. The party has not been going for very long and must last until the end of time. Already the children are weepy and feverish. They all feel sick and want to go home.”

To me, this kind of passionate, imagistic, but precisely argued writing fully captures the folly of the nuclear situation, which is every bit as six-packed, witless and ghastly a barometer of the state of civilization as its namesake on the Jersey Shore. Einstein’s Monsters is more urgently and evocatively written than any number of memoirs, histories, philosophical and political discourses that have marked the silent nuclear countdown since August 1945.

Amis was inspired first and foremost by the luminous, passionate writing of Jonathan Schell, whose classic The Fate of the Earth foretold the irradiated, polluted, slow stir-fry state of the world we now find ourselves living with, and in, for the forseeable non-future we’ve created for ourselves.

The rest of Einstein’s Monsters proceeds from the gauntlet Amis throws down for himself in the opening of his essay, “Thinkability”:

“Every morning, six days a week, I leave the house and drive a mile to the flat where I work. For seven or eight hours I am alone. Each time I hear a sudden whining in the air, or hear one of the more atrocious impacts of city life, or play host to a certain kind of unwelcome thought, I can’t help wondering how it might be.

“Suppose I survive. Suppose my eyes aren’t pouring down my face, suppose I am untouched by the hurricane of secondary missiles that all mortar, metal, and glass has abruptly become: suppose all this. I shall be obliged (and it’s the last thing I’ll feel like doing) to retrace that long mile home, through the firestorm, the remains of the thousand-mile-an-hour winds, the warped atoms, the groveling dead. Then – God willing, if I still have the strength, and of course, it they are still alive – I must find my wife and children and I must kill them.

“What am I to do with thoughts like these? What is anyone to do with thoughts like these?”

His answer is a sequence of stories which all latch upon the varied strands of the nuclear state, the nuclear argument, and the potential nuclear end-game. They explore the issues through beautifully rendered metaphors and allegories that bleed out into re-imagined Earths and states of being. In The Immortal, a man who is slowly dying, along with everyone else, of radiation poisoning, escapes reality by remembering his life as an Immortal being who has witnessed the entirety of the planet’s history. Thus the pettiness of human folly (and achievement) is put into cosmic context.

In The Time Disease, a future colony of pseudo Angelenos have traded in our current obsession for maintaining perpetual youth by any means possible for maintaining a state of premature aging (due to radiation and pollution) under a sky that is boiling with the same kind of nuclear tumescence the Manhattan Project scientists saw in the Nevada desert at the Trinity test. And this is fine by them, because to catch Time, to come down with Time – to become young again, to have hope – means you would have to acknowledge the possibility of Life. Given the impossibility of life continuing in any form we would recognize or desire in this putative future, this post-nuclear world, that would also mean the death of hope. It’s a fitting paradox from which Amis carves a dystopian future far more chilling than any of Hollywood’s creations.

In the early 90s I was planning a radio adaptation for NPR of Einstein’s Monsters, which was to blend the stories with interviews and archival recordings from the frontlines of the nuclear age. The author himself was very supportive of the project. Alas, we were in the early stages of pre-production when NPR decided to scrap all its drama programming, so the project was shelved. But not before we had recorded a demo to give a taste of the series to potential underwriters. This is what you can listen to here. It gives a pretty good idea of what the shows would have sounded like, and stands on its own, I think, as a meditation upon the nuclear problem.

I have always felt that Amis’s atmospheric language, full of rhetorical flourishes and brilliant wordplay, was, like Dickens, ideally suited to be spoken aloud. Therefore, translating his stories into the medium of radio seemed not only feasible, but also desirable. Radio is both an intimate, interior medium, and also the perfect realm in which to let the imagination roam. So it seemed perfect for these kinds of psychological, allegorical and fantastical imaginings that were rooted in humanity’s contradictory nature.

The nuclear issue is a subject whose implications for how we define our species, our place in creation, and our so-called progress through history, let alone our future, are so vast, so paradoxical, so antithetical, that they resist rational argument and easy conclusions with all the slow-burn lethality of fallout. But, just as radiation invisibly suffuses the environment, its tendrils reaching into the fabric of life, initiating its slow rot from within long before physical symptoms of poisoning become manifest, so the idea of nuclear destruction has likewise insinuated itself into our mental DNA. It lingers, it corrupts and, ultimately, it decays everything it touches. For those reasons, this is one of those subjects that demands an experiential argument as much as an intellectual argument to be fully grasped. Which is what Stanley Kubrick was trying to do in Dr. Strangelove, and what, in a smaller way, Radio Einstein likewise intended.

As Einstein himself observed: “The release of atomic power has changed everything except our way of thinking … the solution to this problem lies in the heart of mankind.”

However, as Amis observes, our hearts have already been changed by the specter of the mushroom cloud, but not, alas, in the ways that Einstein was hoping for: “We are all Einstein’s monsters, not fully human, not for now.”

The warning is clear, but will we pay heed?

The signs are not good.

To listen to Radio Einstein, click on this link, or stream via one of the two panels below:

Radio Einstein: