‘Tis the season of mysteries. And in the movie world one of many recurring mysteries is why so many film directors insist on shooting themselves in the foot, music-wise.

As in: wrong music, too much music, not enough music, music in the wrong places, and, in the most peculiar scenario of all, going to the trouble of hiring a great composer and not letting him (or her) do the job.

This comes to mind since I was recently sitting in on a film music class at UCLA, and under discussion was the issue of a director’s and composer’s intent. We looked at scenes with cues that had been shuffled to see how readily an audience picks up on music that was not originally intended for the images it played with. The answer is that film sends pretty strong signals as to what kind of music will work in any given scene, and an audience intuitively gets all of them. So mess with the natural order at your peril.

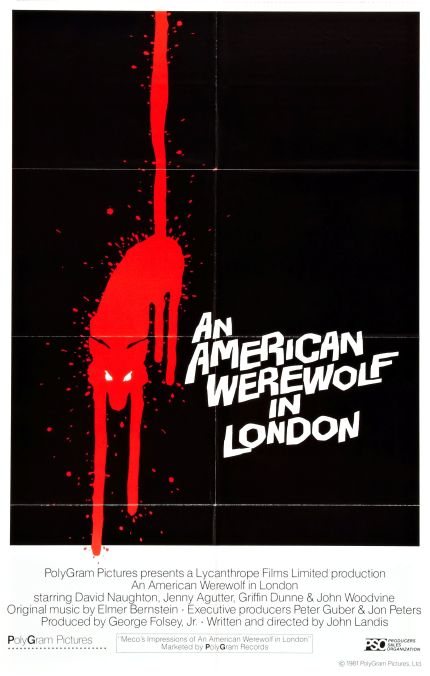

I once witnessed the phenomenon of a director shutting down his composer, and thereby unintentionally hobbling his film, during the sessions for An American Werewolf in London.

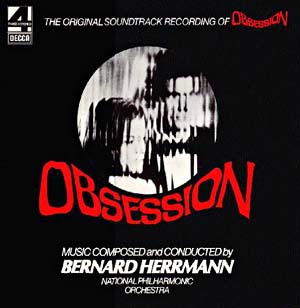

I was at university, incurring the wrath (or at least the healthy skepticism) of my professors by writing a thesis on the film music of Bernard Herrmann. This was not quite the done thing within a traditional academic syllabus, especially since I was attempting to examine the interrelationship between music and image in detail, in a truly cross-disciplinary way. I was certainly no expert in film theory; but I felt I knew enough to make the attempt. The thesis included a cue-by-cue analysis of Citizen Kane and Psycho, but I could not lay my hands on the scores for these films. Herrmann had passed away some years earlier (the night of completing the final mix for Taxi Driver), so I contacted his last producer, Christopher Palmer, in the hopes that he could help me find the material I needed.

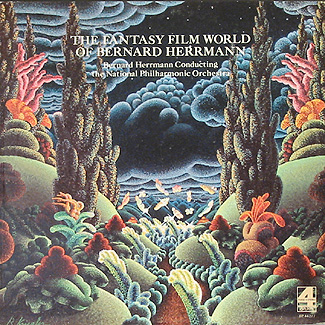

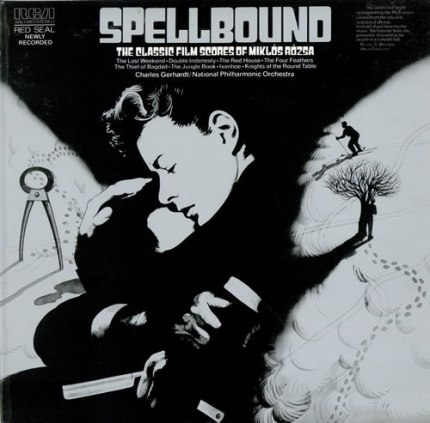

At that time Christopher Palmer was the guy in film music, the only one who was writing about it seriously in the mainstream media, and helping to put together recording projects like the RCA Hollywood Classic Film Score Series and the Herrmann Phase 4 records, touchstones for how to present film music properly on LP. He was also working as an orchestrator and composer in his own right.

At that time Christopher Palmer was the guy in film music, the only one who was writing about it seriously in the mainstream media, and helping to put together recording projects like the RCA Hollywood Classic Film Score Series and the Herrmann Phase 4 records, touchstones for how to present film music properly on LP. He was also working as an orchestrator and composer in his own right.

Back then, few people took film music seriously. Certainly not the music establishment, classical or pop. I was one of a growing number of avid film music fans whose obsession was beginning to ripple through popular culture owing to the chart topping success of John Williams’s scores for Star Wars and Close Encounters. Suddenly one was starting to see dedicated film music concerts taking place, and the RCA series of records had paved the way for new LP compilations. While Williams was the rock star of film music, Herrmann was considered the Old Master — albeit an entirely modernist one.

One memorable day, Christopher handed over bound photocopies of the autographed scores to Citizen Kane and Psycho.

“So, Mark”, Chris said, as my mouth fell open at the sight of Herrmann’s own handwriting on the scores, “Have you ever been to a film scoring session?”

“No,” I replied.

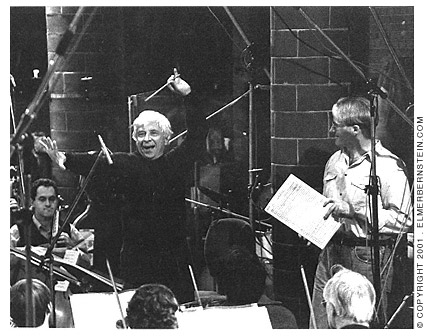

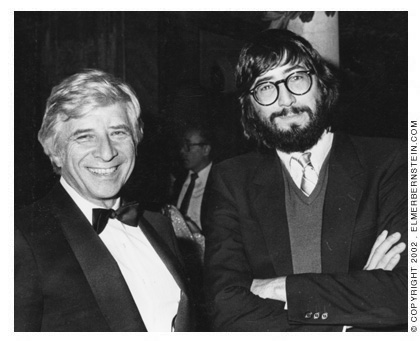

“Well, if you are going to write about film music you’d better come and see how it’s done. I’m producing a session for Elmer Bernstein in a couple of weeks. Come and sit in.”

It turned out the session was around the corner from where we lived, in the London village of Barnes, on the shores of the Thames. The annual Oxford/Cambridge Boat Race used to pass by the high street.

As I walked through the doors of Olympic Studios I had little idea of the roll call of legendary musicians in whose footsteps I was following. I quickly found out, since the equally legendary engineer for the sessions, Keith Grant, had also done the honors for the likes of the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton, and King Crimson. And during breaks he liked to tell stories. Boy do I wish I had written them down.

B.B King (center right) recording in Studio One at Olympic in 1971, with Ringo Starr (far left) plus bassist Klaus Voormann, Fleetwood Mac’s Peter Green on guitar and Steve Marriott on harmonica (all centre left).

Anyway, as Christopher Palmer settled in for the session I noticed a bearded gentleman sitting in the corner of the control room. He wasn’t saying much, at least not yet, but I quickly gleaned he was the director. On hearing his name I got pretty excited, because John Landis had made one of my favorite guilty movie pleasures at university: National Lampoon’s Animal House. Back then, this would screen regularly on a Friday night at 11 to a packed house of pale English students, eager to soak up the anarchies of American campus life, complete with John Belushi gross-outs and topless co-eds, as we munched on greasy chips out of newspaper, smothered in salt and vinegar.

As the session got under way Landis lived up to all my expectations of what a young, hot-shot American director would be like. He was heavily bearded and wore a baseball cap like Steven Spielberg, and was constantly, brashly conversational, full of banter, movie gossip and opinions.

Out on the floor of Studio One, Elmer Bernstein, the distinguished composer of such classics as The Magnificent Seven, To Kill a Mockingbird, and The Great Escape, who had also written the music for Animal House, was revving up his scratch orchestra, a selection of the top studio and orchestral musicians in London. Recording film music is a profoundly technical process, because everything has to time out perfectly. As I watched Bernstein, baton at the ready, scrutinize the screen with its specially prepared clips from the film (cued with dots and moving lines scatched into the film, known as punches and streamers) and repeatedly cue in his musicians perfectly, I marveled at the marriage of musicianship and mathematical precision by which he had composed his cues in meters that ran in tandem with set numbers of film frames. You were never aware of the technological underpinnings: the music flowed with the images as if it had been conjured with no need to perfectly match markers in the film’s action. It was just magically “right”. Never doubt the extraordinary craft and artistry it takes to sync your musical composition to a film, let alone come up with the melodies, harmonies, counterpoint, orchestration that work with the film’s action, its emotion, its sub-text – and do not distract.

Anyway, as the film unspooled it rapidly became clear that it was something quite unusual for a horror film. Two American students were backpacking around England. The tone was light and breezy. And then something odd happened.

Getting lost, they got caught out on the moors at night. There was a full moon. Suddenly they were attacked by a wild animal, and one of them was brutally, bloodily killed.

The hero, David (David Naughton) languished in hospital having his wounds tended to by Nurse Alex. Alex was played by the actress who had been the object of a generation of English schoolboys’ fantasies, Jenny Agutter. Naturally she was wearing a nurse’s uniform, at the sight of which swathes of english manhood were felled on the spot.

David started to have odd dreams, and in the cartoonish nightmare imagery of those dreams it was clear this was a film which was taking the usually predictable horror form and upending it with something fresh, fun, and still very scary.

Nurse Alex starts to take more of a personal interest in her charge, and when he is discharged she invites him home to stay with her. Pretty soon she is tending to more than his wounds.

Now we arrived at the scene which Landis had been proclaiming to the assembled control room was going to “blow the movie out of the water”: the first transformation scene, in which the hero gets fully in touch with his inner lupus. But an odd thing happened. As Bernstein lifted his arms to record the cue, Landis leaned into the mixing console microphone and pressed the talkback button.

“Er, Elmer, that’s fine, but we’re not gonna use it.”

Bernstein shot back: “You haven’t heard it yet.”

“Yeah, I know, but we talked about this. We’re gonna use Blue Moon.”

“Have you got the rights?”

At this point Landis’s equally bearded producer, George Folsey, Jr., chimed in: “We’re waiting to hear back.”

“What if they say no?” persisted Bernstein.

“They won’t”, said Landis, though it was clear from the look he exchanged with his producer that they might.

“Yeah, they might,” said Bernstein, who was as canny an old-hand in the music biz as you’ll ever meet. “Then what’ll you do? You need music here. You might like what I’ve got better”.

“Ok, Elmer,” Landis said, clearly not thinking this was possible.

Bernstein was determined. He raised his arms. Up went the bows. Silence. The film cued up.

The scene began, and so did the music. And both were something else.

The full moon rose. The hero, alone in the nurse’s flat, screamed, fell to the ground. And something started to happen, unlike anything I, or anyone else at the session, had seen on film before.

His clothes ripped, his muscles rippled, his skeleton and skin stretched. But it was all happening on-screen in real time. There were no dissolves as in the classic werewolf movies I had grown up with. A man was violently turning into a very large, rapacious werewolf indeed. It was brilliant.

The work of now legendary make-up designer Rick Baker, then relatively unknown, was extraordinary. This was the first time we saw animated prosthetics on camera, and they were combined with carefully animated visual effects to create a vivid illusion of metamorphosis. Bones expanded, fur grew, nails turned into claws, ears elongated, and eyes darkened as the beast within was unleashed.

In the final coup de théâtre the hero’s elongated wolvine jaw pushed forward, stretching the human face into a fanged canine muzzle. The newly birthed American Werewolf howled to the moon.

And with every extravagant metamorphosis on screen the music more than kept pace: it drove the transformation. It gave voice to our horror, and the character’s terror, at what was happening, at the same time as capturing all the grand beauty of the spectacle. As the sequence ended and the music smashed to its conclusion, the orchestra and control room erupted into applause. This is a rare thing. London session musicians have seen and heard it all. But it was clear that what we had just witnessed, music and image together, was a showstopper. The combination of groundbreaking visuals and barnstorming music was one for the ages. It would, in the words the director had spoken earlier in the session, “blow the movie out of the water”.

Except…..

The orchestra and conductor/composer waited for the pronouncement from the control-room.

“It’s great, Elmer.” John Landis’s voice was authoritative. “But if I get Blue Moon I’m using it. Let’s move on.”

No one made a comment, but we all knew what we were thinking.

What are you thinking?

A year later, venturing into a cinema to see the completed film, I secretly prayed that the rights to Blue Moon had been denied, and that the world would see what I had seen and heard that memorable afternoon in Olympic Studios. As the film neared the transformation scene I braced myself. The hero pottered around Jenny Agutter’s flat, the moon rose and –

“Blue moon…..”

The unmistakeable tones of Sam Cooke rang through the theatre. As the hero submitted to his bodily eruptions I kept hoping John Landis had come to his senses and would segue into Bernstein’s apocalyptic cue. But no. I was left to intellectually appreciate the director’s ironical juxtaposition of music and image, rather than submit to the terror and awe-inspiring horror of a man becoming a beast, red in tooth and claw. The transformation, while still striking, was robbed of its ultimate animal ferocity. It became oddly prosaic, fully serving neither the story nor the audience. Since this was a film that, for all its jokiness, had at its core the tragedy of a man destroyed by his true nature, then playing down the moment when that nature emerged for all the world to see seemed an odd choice. Knowing as I did what the scene could have been with Bernstein’s cue, it was something worse than a missed opportunity. It was a regrettable example of a director remaining wedded to his original concept, rather than listening to what the work itself and his highly experienced collaborator were telling him.

In the end, the scene did not “blow the movie out of the water” — but it certainly blew.

FILM MUSIC AFICIONADOS AND COMPLETISTS, PLEASE SEE MY EXPANDED THOUGHTS ON THIS IN THE COMMENTS BOXES BELOW.

ADDENDUM (September 2019): As you will see from my comments below, a lively discussion took place on the site FSM (Film Score Monthly) after this article was published. We all agreed that the missing cue turned up as “Metamorphosis”, later re-recorded by Nic Raine and the Prague Philharmonic. An enterprising soul, Mr. von Kralingen, has now synced that cue with the original scene, more or less as it would have originally played — and here it is. Enjoy!

Related articles

- Director John Landis attacks Hollywood studio system (theguardian.com)

very interesting post – this is my working life to a T… the funny thing about the film making process is the filmmakers are usually the ones who experience the sorrows associated by the missed opportunities; and in fact, if you had not heard that cue (and boy am I curious to hear it…) you probably would have thought that the juxtaposition of Blue Moon and the transformation was a brilliantly ironic response to such physical horror.

it took me years, YEARS, to get over the experience of Romero + Juliet and I finally did when a friend pointed out how wonderful the film was and I forever was reminded that general public have no awareness of the sausage factory and as such their cut of cured meat tastes just fine, thank you very much.

having said that, films have to live the life they are born to live for the general public – there is no other way. if AMWIL came with a disclaimer that the transformation scene isn’t as good as it could be, well would the film would be remembered as less than the classic as it is?

as an aside, my first scoring session was also at Olympic studios for the before mentioned R+J….

Thanks so much for chiming in, Vordo! (and thanks for reading). No doubt Landis believed (and still does) that going for an ironic juxtaposition was preferable to the more obvious “on the nose option”, which is what Bernstein scored. But I believed then, and I believe now, that it was a smart-arse move, a case of the director being more interested in polishing his auteur credentials (subverting genre within the Hollywood system) than serving the story. (The story, at this point in the film, was about out-and-out terror and horror — and that was what Landis had shot in his rigorously detailed transformation. And, as I write above, he kept talking about “blowing the movie out of the water”. Was this really the place to create a music/image juxtaposition that distanced the viewer?). This kind of “cleverness” is a condition that has been dogging American directors since the auteur theory was propounded, and we see it derail many a Hollywood film — those of Baz Luhrmann included. I’m all for using sound and music to oppose the image, but it has got to work within the context of what the story is doing at that moment.

One of the reasons a good director should choose to work with top collaborators is not only so that they will give him great ideas and make him look better than he is (ahem), but also to help curb such wayward tendencies. Obviously the director (or studio) is the final arbitrator, but he should think smartly and learn to listen closely to the experts around him who, if he has “cast” them correctly, will want to serve the interests of the film to the nth degree. The director’s job, first and foremost, is to have a clear vision of what the film and story are, to communicate that vision to his collaborators, and know when the sweet spot is being hit.

Your point that ultimately the film must be experienced and judged “as is”, rather than in another putative incarnation, is, of course, true. It’s just that, in this instance, I happened to see a superior cut, as it were, and the reasons for why that cut isn’t the final one are worth illuminating and considering. It’s not the first time that a director has ignored his composer at his peril (and good film composers can teach a director a lot about his film). Think Hitchcock’s firing of Herrmann from “Torn Curtain”.

On a more personal note, I will point out that working with you on my film was a fabulous experience. One dreams of having these kinds of truly inspirational collaborations in which bringing out as many facets of the work is the shared goal. Baz was luckier than he knows to have had you on the project but, like Landis, it sounds like he got to a point of no longer listening in the way he should have been. We can all get a little deaf sometimes.

Wow! What a great article and what an amazing little insight into such a well known moment in cinema. I do have to play the devil’s advocate and say I completely disagree with you though (insert smiley devil emoticon here). I have long been a fan of horror films and I can think of no other moment that so plainly bewildered me as a viewer. Granted, I was but the age of 11 when I first saw the film, I can still remember it to this day. What you describe as a juxtaposition I would describe as immersive and completely warranted. One of my film theory professors once stated that at its best, the horror genre works as ‘A nightmare in the daylight’. I’ve always held onto that. Terror when you least expect it and nowhere from which you can hide. So, while this scene is clearly at night under the full light of the moon, Landis could have easily set this transformation in the woods, or a London alley or a darkly lit room with moonlight pouring through – please see The Howling Transformation…

But Landis fights that cliché and we are set to experience the transformation with David in the fully lit quaintness of an English sitting room. No stylistic lighting or fog or shadows whatsoever!

And what furthers the shock of this fully viewable horror is the lack of an orchestral score – leaving us with neither foothold nor compass to help us predict the trajectory or duration of the terror – rather we are pulled further into David’s body by the incredible score of boiling flesh and stretching bone as David’s expression questions so brilliantly (as he stares directly into the camera), why? And we are left helpless in wonder as to what the Hell is happening and when is it going to end?

That is the brilliant difference. That Landis caged him in normalcy. Location, light and song. Not to juxtapose but rather to alleviate us of our preconceptions – elevating the turmoil that David (and the audience) would experience by the horror happening within. The music, playing as it would on a car radio if we were left dying in a rollover accident, without empathy or compassion to the horror happening inside. All conceived not to juxtapose, but to elevate. That is why it is so terrifying.

I throughly agree with you. I love Elmer Bernstein’s music in this film and even like “Metamorphosis” very much but I actually was blown away by the juxtaposition of this frightening scene with diagetic music (that’s how I heard it). I was really struck by that when I first watched the film. Like the insane Picadilly Circus scene with carnage all over the place, this entire film is a juxtaposition of horror, reality, and fantasy. I think this was the case of a cue that would not have fit this movie at all, and the video posted pretty much proves it IMHO.

Thanks for arguing your case so cogently, Ryan, and I imagine Landis would heartily agree with you. All I can say is that all of the qualities of the scene you argue for remained with Bernstein’s original cue as I heard it. His music merely intensified the moment in a way that felt absolutely right. While I appreciate the ironic juxtaposition that “Blue Moon” brings to the scene, it nevertheless also takes you out of David’s agony in a way that I feel is detrimental.

It’s such a wonderful experience you shared – thank you again for bringing it to us! The more I think about it, the more it pains me to know that these notes have been lost in the folds of conceit. While it will always remain a favorite moment in cinema for me, I will forever wonder what magic was left behind. Maybe Landis will grace us with the alternate recordings on a 40th Anniversary Blue Ray Edition. : ) Here’s a hopin’.

Well as a result of posting this on Film Score Monthly I received a lot of feedback. My resulting comments are below.

I have abbreviated the extent of the conversations that took place between Landis and Bernstein in my account in order to convey the essence of what the principals were thinking, and what took place, succinctly. For the purposes of completeness, I will now expand.

I agree, you would expect for the scoring of this cue to have been discussed prior to the session, and for these conversations at the session itself (which I report) to take place privately, but they didn’t. They took place partly over talkback and partly in the control room. The atmosphere was frosty.

Going into the session it was clear that the rights had not been cleared for “Blue Moon”. In fact I think they recorded a cover version with another singer but in the same arrangement as the Sam Cooke, just to be sure. Landis was convinced this was the way to go with the scene. But Bernstein strongly disagreed, and it was clear from the extent that producer George Folsey, Jr. got involved that this had already been the topic of heated discussion during spotting sessions. My read on all of this was that Bernstein had gone away and composed the cue anyway, in the hopes that by having Landis hear it he would convince him. The combination of those visceral visuals and Bernstein’s fabulous score did, indeed, “blow the movie out of the water.” I was familiar with enough film music, and other music from the classical canon, to know something remarkable when I saw and heard it.

It was clear that Landis and Bernstein had a good working relationship and friendship, but this cue sorely tested it. Bernstein was adamant that his score was the way to go, and I agree. The movie up to this point deftly played with tone, in all the ways that made it an entirely original and fresh contribution to the horror genre. But in this scene the film doubles down on the horror, and Landis filmed it as realistically as he could. And this is how he talked about it during the session — he wanted the audience to go apeshit. With his score for the scene, Bernstein enhanced and amplified the vividness of the transformation to the nth degree. Like I say in the article, that a studio full of jaded studio musicians applauded the way they did was ample testimony to the effectiveness of the music.

But Landis’s reaction was almost dismissive (even as he told Bernstein it was a great cue). He said this was NOT the direction he wanted to go in. Remember, this was a young director at the top of his game, feeling his oats, knowing that he had a potential hit on his hands. And he conveyed his thoughts with a certain amount of brashness and vigor. Bernstein, however, stuck to his guns. He believed in his music, and he believed it was what the film needed in the scene. He was not happy, at all, to have to move on.

All I can say is that every time I see the film and we come to the transformation scene I sigh with disappointment. Imagine what the shower scene in “Psycho” would be like if you just heard a song on the radio in the background and Janet Leigh screaming, rather than Herrmann’s music that melds screams and murderous jabs into a singular musical gesture, then plays the process of dying in those jagged disintegrating musical phrases as the life drains from Leigh’s eyes, and the bloody water drains from the shower. Bernstein’s cue didn’t quite reach those expressionistic musical heights, but losing it from the transformation scene did detract from the film in what has become, rightly, a celebrated few minutes in film history.

Going into the session I was already familiar with the tensions between composers and directors that had played out on celebrated projects, like “2001” and “Torn Curtain”. I was astonished to find myself with a ringside seat at one such disagreement. Of course, none of us knew that the film would become such a classic, and therefore of much interest to each new generation that saw it. I have been astonished at how passionate an interest this little article has produced. I just had an interesting story to tell, which I felt illuminated something of the inside process of film scoring, and just how tricky a thing it can be to get right. Well, now it seems some light has been shed on a film that is much beloved, and on a composer who was one of the greats working in his field. It is also important to note that Landis felt strongly enough to stick to his guns when under a lot of pressure to change his mind, even at the risk of upsetting one of his closest collaborators, and we should commend him for having a vision and sticking to it, even if we are not entirely in agreement with the outcome. It’s still a fabulous movie! For all these reasons, I am very glad it was a story I was in a position to tell.

Another contributor to the message board pointed out that on an album of Bernstein’s music a track was recorded by the City of Prague orchestra called Metamorphosis. No-one really knows what that music is, since it contains elements of the “Thriller” music that Bernstein composed for Michael Jackson’s video. I took a listen and, lo and behold, it turned out that the first three minutes of the track are indeed the missing cue from “An American Werewolf in London”. My comments upon the track are below. It can be found on amazon (and also, I believe, on spotify).

The first 3:00 or so is what I heard recorded at Olympic. The rest is more generic, and maybe comes from another killing scene. The transformation scene visually is the same now as it was at the session, nothing was cut out. I do not recall there being music in the next scene in the movie, but I could be wrong.

I cued up the first three minutes of “Metamorphosis” against the movie and it was a salutary experience, which I recommend to any student of film music. The music is recorded a little on the slow side — you will have to finesse it so that the beginning of the transformation itself (0:36 in the music track) coincides with David screaming and falling to the floor. Even making allowances for occasional misalignments, you really get a sense of what Landis lost by sticking with his use of Blue Moon.

Bernstein’s music keys right into David’s terror as he literally loses control of his body, and the close-ups when he looks straight to camera have an added intensity: the music plays his emotional journey beat by beat, all the while simultaneously conveying the violence of the physical transformation.

In so doing, Bernstein picked up on Landis’s intuitive desire for some sense of “distancing” (i.e. not playing the cue exclusively for on-the-nose horror), which I imagine would have been expressed in the spotting sessions and earlier discussions. Instead of launching full-on into the violence and horror of the scene, he played instead on this sense of David’s torture and agony. THIS is why the cue is so effective, and why it gives you an emotional kick lacking in the final film version that Landis approved. You can hear it in the string phrases from 0:50 to 1:10. Then the music returns to that sense of moonlight magic from 1:11, before returning to the hammer-crunch chords of doom at 1:28 (and can you not continue to hear David’s inner screams throughout these bars?) From 1:50 on the music locks in with a vice-like grip, conveying musically the series of bodily distortions we are seeing onscreen.

By the time the beast within is in control you will notice how the music becomes terser, almost mechanistic in its gestures: the human has been completely lost. The wonderful downward brass glissandi (maybe a Christopher Palmer touch) coincide with the two thrusts forward of the animal muzzle. Then it’s all over and the music settles onto a static chord of resignation as the camera pans across the werewolf crouching on the floor.

None of this emotional nuance and progression is present in the version we see in the film as is: it’s just a scene, albeit an effective one, of horror. Those close-ups of David read to a degree, but “Blue Moon” on the soundtrack offers only a general, ironic commentary. It functions like source music. By contrast Bernstein’s music in the rejected cue tracks David’s experience and emotions from moment to moment in a way that we do not have to guess — we feel the emotions with him.

Not every film demands this kind of music scoring, but when it does, and the composer does it well, the results can be spectacular. The unique alchemy that takes place between image and music in such cases is not to be taken (or shed) lightly.

I cannot speak to the relationship between any of this music and what is heard in “Thriller”. As to Landis’s saying on a DVD that the music was recorded in a former church, maybe he was confused because the studios stood on Church Lane. The building had originally been a theatre. I do not recall the use of an organ during the sessions, although maybe something was recorded separately. Olympic was one of the go-to studios for film scoring in London at the time because the room had a great acoustic, and the legendary engineer Keith Grant would run the board.

First, thank and bless you for sharing this terrific and terrifically told inside story about one of my very favorite movies. I’m in your debt, and jealous as hell that you were there.

I was 12 years old when American Werewolf came out, and it made an indelible impression on me. I’ve seen it countless times since (and spent a little time with John Landis fawning it).

Like any sane film music lover, I deeply admire and respect Elmer Bernstein. The Metamorphosis cue is brilliant, ferocious, and a sterling example of his art. If it had been used, I’m sure I would have loved the movie as much as I did.

But it’s not right. It’s not right because it’s not what Landis wanted, and he was the custodian of what was right for the movie. At 12 years old, I didn’t know anything about ironic counterpoint, unironic counterpoint, nor any other kind of counterpoint. I only knew that the transformation was REAL in a way nothing like it before had ever been REAL. And I’m convinced a lot of that had to do with the scene eschewing traditional “scary” music and rooting it in a world I knew and understood.

Subjectivity is a trap and I admit that nostalgia must play a factor in this. But in all honesty, having watched the scene synced with the Bernstein, Blue Moon simply FEELS more like the movie. It’s just right. As I see it, Landis exhibited great discipline rejecting such powerful music in favor of his vision. Being a director is being constantly engaged in a tug of war between the movie you imagined and the movie you’ve created, and knowing when to give and when to keep pulling is what the job is all about. It’s not easy, and you’re always on the knifes-edge of potential regret. But I, for one, am glad that in this case Landis kept pulling.

The composer I worshipped above all was Jerry Goldsmith and he famously derided Stanley Kubrick for dumping Alex North’s score in favor of his temp cues. And as much as Jerry could do no wrong in my mind, he was wrong about that one.

Again, thank you so much for this. If memory serves you, I’d love to hear anything else that comes to your mind.