At one point in my errant school career I was receiving so many lines as punishment (“The rules of Latin grammar are to be approached with diligence, and ignored at one’s peril”, or “I must not flick paper pellets at my fellow pupils”) that my mother summoned my form teacher and took him to task:

“You seem to have lost control of my son. I have not.”

“Er…..”

“And why do you set him all these lines to write? I cannot think of an undertaking of less merit that wastes so much time to absolutely no purpose.”

“That’s the point….”

“Well it seems a singularly useless one. Why, since he is dedicating so much time to making up for his errant ways, don’t you give him something useful to do?”

“What would you suggest?” inquired Mr. Gapper, with the mildly condescending tone that teachers sometimes use when addressing recalcitrant and demanding parents.

My mother, however, was now so wrapped up in her theme that she was oblivious.

“Have him learn something by heart. Like poetry for example.”

“Poetry….?”

“And, since he is clearly a repeat offender, why don’t you pick something long, so that you don’t have to keep on coming up with new suggestions. How about The Rime of the Ancient Mariner? That’ll keep him busy. It’s in rhyme, so it shouldn’t be too difficult for him to remember. And maybe he will pay heed to the moral of the tale”, at which she fixed me, like the Mariner does the Wedding Guest, with a glittering eye.

Thus having settled the matter of how I should be disciplined, she swept imperiously away. Mr. Gapper let out a deep sigh of relief. Or was it anguish? Or a bit of both. My mother could have that effect on teachers (as well as bankers, accountants, and doctors). I think he felt a little sorry for me.

The upshot to this change in my disciplinary regime was that by the age of 13 I knew most of Coleridge’s 625-line poem by heart. And, while I enjoyed quite a sense of pride at this accomplishment, I had also discovered that learning poetry was much harder work than writing lines, and my behaviour in class had improved considerably as a result.

Little did I know that this unusual addition to my school resumé would one day prompt one of the most enjoyable creative experiences of my career in radio. In 1988 I was working as a producer at WBUR-FM in Boston, one of the flagship stations in the NPR system of member stations. My work largely consisted of writing and producing a range of music programming for both local and national broadcast, but I had also started directing, producing and writing radio dramas. These had, surprisingly, turned out to be very successful in terms of station carriage and, more importantly, attracting corporate underwriting. All this was very unexpected, because the popular wisdom in America was that radio drama was dead. Well, in our own small way, we were proving them wrong.

Boston University’s College of Communication, which housed WBUR at the time of our recording

The reason any of this was happening at all was due to the support and vision of our station manager, Jane Christo. A feisty, no-nonsense lady from Maine, she had taken WBUR from being an outlier in the NPR universe to the hottest station in the system, with a kick-ass news department and a little show called Car Talk that was just starting to make an impression on the national airwaves. One day Jane summoned me to her office and said: “We need a special for Easter. Can’t be religious, but something with some sort of Easter theme might work. Any ideas?” I thought for a moment, and suddenly the literary punishment of my errant schooldays came to mind.

“What about The Rime of the Ancient Mariner? It’s got a spiritual message of the importance of loving all things great and small, and it’s classy.”

Jane, who always had a keen sense of the marketplace, hesitated: “Isn’t that a little too rarefied? I mean, a long poem written over two hundred years ago?”

“Don’t worry, Jane. I’ll make it sexy.”

‘Sexy’ was one of Jane’s trigger words. If you said a program would be sexy you were assured of her full attention.

“Okay. Surprise me, Mark.”

As I left her office I had just enough good sense to realize I had made a somewhat rash promise. I had proposed the following. Recording an epic poem written in rhyme about a salty old sea dog shooting an albatross, thereby bringing down a curse upon his ship and fellow sailors that ends up killing everyone except him; he goes on a voyage into purgatory with attendant supernatural terrors, where he learns to respect the value of mercy and respect for all his fellow creatures; nevertheless he has to wander the earth for the rest of his life to tell his tale to random strangers, to warn them not to go around shooting albatrosses etc.

And I was going to make this sexy? What was I thinking?

What indeed! Well, the first thing I decided was I was not going to do a straightforward reading of the poem. No matter how good the actors were (and I had worn out an old record of Richard Burton reading the poem which was, needless to say, the nonpareil), the result of recording it in this fashion was unlikely to be described as sexy. Even if Richard Burton had been available.

No, this had to be a truly radiophonic version of the poem, something which used sound creatively to bring Coleridge’s fantastical journey to life.

I also decided this could not be a straightforward “words with sound effects” deal. That was the standard BBC Radio approach, and it would not do for this project. Funnily enough, the place where I had heard the most consistently interesting sound work growing up was on TV, on a little show called Doctor Who. Sounds and music suitable for a time and space travelling nomad in a police box were provided by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

This enterprising collective of composers and sound artists using a hodge-podge of synthesizers and electronics were the quaint British version of places like WDR-Cologne and, later, IRCAM at the Pompidou Center, where avant-garde composers like Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez were redefining music and how to use the recording studio.

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop was mostly doing the honors for daleks, cybermen and assorted denizens of the Doctor’s travels. Its work filtered into other areas of the BBC’s line-up too, and every so often I would hear a radio play that went into the more experimental zone as a result of featuring the Workshop‘s sound experimenters.

But at WBUR-Boston we had no such equivalent or elaborate electronic gizmos. People’s reaction to seeing the main studio and control room echoed that of Arthur Dent seeing the interior of a spaceship for the first time on The Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: “I was expecting gleaming control panels, flashing lights, computer screens…. Not old mattresses!” We didn’t even have a sound effects library. What we did have was a staff of incredibly creative engineers, all of whom engaged in a range of eclectic musical and recording gigs outside their regular jobs. I already had a hunch that one particular engineer was the right fit for the job. Rick Wolf moonlighted as a performance artist, and I had been impressed by his one-man show which incorporated very creative, often interactive, sound design. An idea was already forming about how I was going to approach the project, and I broached it to him. He got it right away, and revealed that he had a decent 8-track recording set-up at home, with some good basic outboard gear, in particular reverb and delay – essential items for what I had in mind.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Coleridge’s poem, although written in traditional rhyming verse, was, in fact, nothing more or less than a phantasmagorical trip. It was a hippie version of a morality tale, complete with acid visions, out-of-body experiences, spirit visitations and voices, natural cataclysms, and zombies. Remember, this was the same poet who had written “In Xanadu did Kubla Khan / A stately pleasure-dome decree….” and its succeeding hallucinatory verses after tripping on opium, only to be awakened from his spell by the intrusive knock of a visitor. The spell broken, he couldn’t finish the poem.

Xanadu

What I had decided to do was to tap into the fantastical, hallucinatory aspect of the Mariner’s voyage via the language, and use the words themselves, as spoken, to generate a trippy sound world. We would record the poem as well as we could, then manipulate the recording, breaking down words and the voices speaking them into pure sound. This would then weave aural textures around the actors’ voices, reflecting the emotion, and supernatural elements, of the story. I would also add music, timed carefully to flow with the contours of the sound and the events of the story. There would be no sound effects per se beyond the bare minimum at the opening and close of the tale, when we are in the real world. Once we entered the fantastic realm, it would all be pure sound and music. By sampling the speech to create its own music track, as it were, the sound world, at its core, would have a pure, organic quality, all tied into the primacy of the actors’ voices and the words they were speaking. The language would, in effect, generate the “trip”.

I was, in part, inspired by what the director Stanley Kubrick had done in the Stargate sequence that leads into the final section of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Here, Kubrick needed to create a visual correlative for, and narrative of, travelling into another dimension of space and time, making contact with a higher intelligence. Through this contact, the astronaut hero (and, by implication, Mankind) would be taking an evolutionary step forward.

Working with his brilliant visual effects supervisor, Douglas Trumbull, Kubrick devised a slit scan-device in which light was broken down into a constantly morphing, travelling array of colors, shapes, and designs. Essentially they deconstructed light itself, as it passed from source via lens to the film’s emulsion — the building blocks of the filmed image. It was both the perfect method, and metaphor, for what was happening in the story.

When 2001 first played in cinemas in 1968 it rapidly became a favorite for audiences tripping on LSD, and was even promoted as “The Ultimate Trip”. Well, in its own time, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner was similarly an exploration of different stages of consciousness and supernatural experience. Deconstructing and reconstructing the building blocks of the medium I was working in — language, voices and sound — seemed the perfect way to dramatize it for radio, just as deconstructing light had been the right path for Kubrick.

There was one significant challenge, though. We needed to find an actor who could not only handle the tricky task of speaking rhyming couplets in such a way that they would not become tedious, but also would have a voice one could believe as that of a grizzled sea-dog. It would also have to be rich enough to generate the kind of varied sound palette our approach demanded. Even if Richard Burton himself had walked into the studio I doubted he would have been right for the job. I needed the radio equivalent of a method actor, someone whose voice “lived” the part.

The whole enterprise could have foundered on this point, but by some miracle a friend of mine who was an actor and worked part-time at the station said he knew just the person for the job. And boy did he. One memorable afternoon, into the station walked Mr. Brian Way, a well-known member of the local acting scene, and the moment he opened his mouth I knew we had our Mariner. He fairly breathed the swells of the Atlantic, and his voice communicated several lifetimes’ worth of rich experience. I told him what I wanted: “You are the Mariner. You lived this story. I want you to tell this tale as if your life depended upon it. With every word you speak you relive this horrendous experience that you must repeat endlessly to prevent others from making the same mistake you did. Do not hold back. Relish every word, every syllable. The language is the music by which you take me into your memory, your suffering, and your vision of redemption.”

Brian’s eyes glittered with relish already.

For the role of the narrator and a few other incidental characters I turned to students and faculty who were at Boston University’s College of Communication. We had already worked together on a few other radio drama projects, and they leapt at the chance to do something so unusual. Amongst them were the Dean of the School, Ronald Goldman, who lent a splendidly resonant baritone to the proceedings, along with an ethereal whisper for one of the spirits that visit the Mariner’s dreams. His colleague, Leila Saad, was Egyptian, and her rich accent was perfect for the nightmarish figure of Life in Death who wins the Mariner’s soul in a game of dice. The cast was rounded out by Robert Reames as the Narrator and Payman K. as the Wedding-Guest, and other assorted roles.

“‘The game is done! I’ve won, I’ve won!'”

The day of the recording arrived. From the moment we rolled tape Brian Way transfixed everyone in the studio. We hardly ever had to do second takes. The poetry was in his bones, and he rode the tricky rhythms of the couplet form effortlessly. Needless to say, the quality of his performance made everyone else bring their A-game.

Once Rick and I had edited together the spoken performances we repaired to his studio. We began the process of molding the recording with delay and reverb to create the fundamental, as it were, of the soundscape. As the voyage began the voices were untreated, but once the storm hit and the ship entered the frozen wastes we began to introduce our effects. After the Mariner has killed the albatross and the story enters its supernatural phase we began the process of carving loops and feedback out of the words.

It was akin to creating an orchestral score out of one instrument, harmonies and counterpoint working together, never against each other, to convey a consistent, unified aural argument.

Simultaneously I started to pick out music to accompany the journey. I had settled on two works.

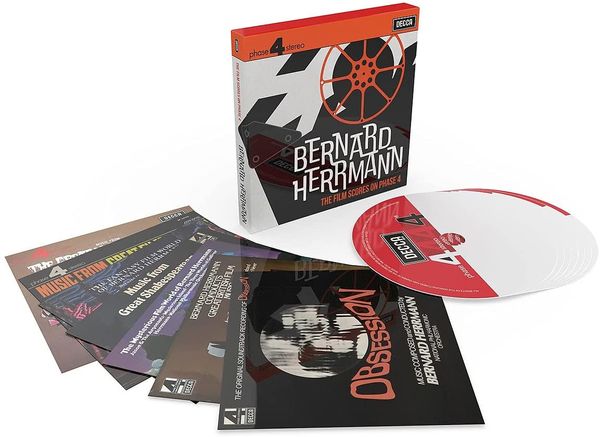

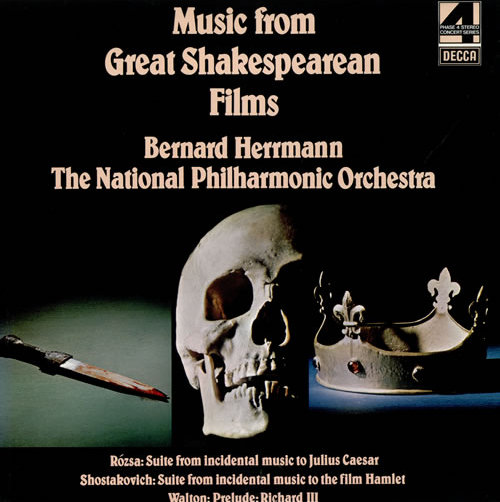

First, Vaughan-Williams’ Sinfonia Antarctica, which was based on the score he had written for the film Scott of the Antarctic. It was as if the music had been specifically composed for Coleridge’s poem, so perfectly did its moods, rhythms and textures reflect the Mariner’s ordeal. Second, selections from Bernard Herrmann’s score for the film Journey to the Center of the Earth, another musical depiction of an epic journey and fantastical visions, perfectly dovetailed with the Vaughan-Williams. For a scene where spirits discuss what the cursed Mariner’s fate should be, a piece Herrmann had composed to evoke a lost subterranean ocean, using organ and vibraphone, conjured the necessary otherworldly quality. In a few places I also added a little extra spice with electronic sounds and motifs of my own devising.

Whenever our spirits flagged as we assembled the tracks, we had only to listen to Coleridge’s words and Brian Way’s extraordinary performance to feel rejuvenated.

Finally, after completing the mix, Rick declared it time to listen to the thing properly, all the way through. We doused the lights, lit candles, lay on the floor and cranked the volume. We cracked open a bottle of wine. I’d like to think Rick lit up something stronger, though honestly I cannot remember whether he did or not. Certainly it was the kind of show that would gain extra dimensions through “filtered” listening. Using headphones in darkness is also highly recommended.

Artwork for Iron Maiden’s version of Rime of the Ancient Mariner

After the broadcast we had listeners calling and writing in to declare their love for the program. Teachers asked for copies to use in the classroom. It won a bunch of awards. Jane, my boss, delivered her verdict: “Sexy!”. The show was repeated for a number of years, on far more stations than you would expect for such a quirky, “old world” venture. A 200-year-old poem was a certifiable hit, and I quietly thanked my mother for her intervention in my disciplinary regime at school all those years ago. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner remains one of my favorite pieces of radio work. I hope you enjoy it too.

You can listen to the complete dramatization of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner here, with the accompanying drawings by Gustav Dore.

Or you can access it for streaming, or download, on my Soundcloud page.

Frontispiece of 1876 Edition