Ever wondered what an alien invasion sounds like?

Well, 75 years ago, on October 30th 1938, large swathes of America got to find out. Listeners to CBS radio heard their regular programming interrupted by news reports of strange eruptions in space, and objects crashing to earth. That was only the beginning. It wasn’t long before the eastern seaboard was gripped by panic, and people were flooding into the streets – trying to escape what they thought was a full-scale Martian invasion.

Meanwhile, word of the panic spread to the CBS studio, where Orson Welles and his Mercury Theatre company of actors were gleefully rampaging their way through Howard Koch’s adaptation of this science-fiction classic.

With little inkling of the furore outside, Orson Welles decided to defuse the situation. After speaking the last scripted lines of Professor Pierson, he announced – “out of character” – that the program had “…no further significance than the holiday offering it was intended to be”. With an impish smile in his voice he concluded: “And remember, please, for the next day or so, the terrible lesson you learned tonight. That grinning, glowing, globular invader of your living-room is an inhabitant of the pumpkin patch, and if your doorbell rings and there’s no-one there, that was no Martian… it’s Halloween.”

They went off-the-air. Then, leaving the cocoon of the studio, Welles was confronted by the magnitude of the panic he had unleashed. The laughter died on his lips. Even the master showman had been blindsided.

History was made that night. It was the first major media “Got ya!” and it turned Welles, already a cause célèbre in the theater world, into a media star. Hollywood came calling with an unprecedented contract, which resulted in the equally unprecedented innovations of Citizen Kane and a film career of, in equal measures, maddening genius and frustrated intentions. Maybe the Martians had the last laugh after all.

When I was producing radio theater for National Public Radio I had occasion to revisit that legendary night of broadcasting. L.A.TheatreWorks decided to record an updated version of Howard Koch’s script for Orson Welles with members of Star Trek, old and new generation.

Thus Wil Wheaton and Gates McFadden joisted at the microphones with Brent Spiner, while Mr. Spock himself, Leonard Nimoy, took the central role of Professor Pierson.

His voice commanded the airwaves in a manner all of these Hollywood old-timers, who grew up doing radio, theater and live TV, have to themselves. You felt every syllable of his awe and fear in the face of the alien invader. Researching the script for a subsequent rebroadcast on Halloween (naturally) I delved into the history of that original transmission, and of the book that started it all. There were a few surprises along the way. (In particular, Simon Callow’s excellent biography of Orson Welles provided a wealth of anecdotal material and pertinent observation, some of which I reference in the following.)

His voice commanded the airwaves in a manner all of these Hollywood old-timers, who grew up doing radio, theater and live TV, have to themselves. You felt every syllable of his awe and fear in the face of the alien invader. Researching the script for a subsequent rebroadcast on Halloween (naturally) I delved into the history of that original transmission, and of the book that started it all. There were a few surprises along the way. (In particular, Simon Callow’s excellent biography of Orson Welles provided a wealth of anecdotal material and pertinent observation, some of which I reference in the following.)

H.G. Wells at the microphone in 1929

Science fiction, it is fair to say, was invented by H.G. Wells, along with Jules Verne.

Wells had found a new way to explore the greatest aspirations and deepest fears of humanity through the metaphors of science and technology, and the worlds they were unveiling. But he knew the quest for knowledge was a double-edged sword, and fully exploited the unease that walks hand-in-hand with our boundless curiosity for the unknown.

For his most famous prophetic warning of the fragility of civilisation, Wells exploited the current fascination with the possibility that “We are not alone”.

In 1894, the planet Mars had been near enough to Earth to be observed in detail. The Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli identified linear patterns on the surface that he named “canalli” which, in Italian, means “channels”.

A page from Schiaparelli’s diary, 1890.

But in one of the great mistranslations of all time, English-speaking peoples thought he meant “canals”, leading to widespread speculation about the possibility of life on the red planet. Another observer claimed to have seen a strange light flashing on Mars, fuelling the debate.

Schiaparelli’s map of Mars, 1888

Meanwhile H.G. Wells was making his own observations closer to the Earth. Germany had unified, and embarked on a program of militarization. Wells and others feared this might lead to war in Europe. Inspired to fire his own warning shot, he turned to the public’s fascination with the possibility of life on Mars as a way to warn of the danger.

Title page from 1913 edition

In his hands, the utopian vision of disparate cultures uniting, of civilisation reaching beyond the stars, disintegrated in the beam of a heat ray.

1899 Cover Art

Instead humanity faced the nightmare of a pre-emptive first strike by superior technologies of Armageddon, serving masters whose only thought was: what was the point of sharing when you could have it all?

Title page of First Edition, 1898

Wells told his fantastical fable in a semi-documentary style, giving it a credibility and power it might have otherwise lacked.

When, in 1938, Howard Koch came to adapt War of the Worlds for the radio broadcast by Orson Welles and his Mercury Theatre on the Air, he faced two major challenges. How to find a modern-day equivalent for the book’s hyper-realistic style, and how to overcome the dated, provincial aspects of the novel because of its period setting in England. He decided to move the action to America, randomly selecting the New Jersey village of Grover’s Mill as the site of the invasion. From then on, realistic imperatives drove the script. Koch made the medium the message, turning radio’s ability to broadcast live events as they happened into an integral part of telling the story.

Welles with John Houseman

It was a brilliant narrative strategy, but Orson Welles and John Houseman, co-founders of the Mercury Theatre Company, were initially underwhelmed by the script. Preoccupied by what had turned into a hellish theatre production of Danton’s Death, they picked at the script in their usual way, pulling it about structurally and demanding more realism. Welles dismissed it as “corny”. A lot of emphasis was placed on sound effects, in the hope they would distract attention from the thinness of the piece.

Despite – or because of this – Welles and his fellow actors went for broke, playing it for all it was worth.

Everything was pushed to the extreme – the apparent breakdowns in transmissions, the desperate eruptions of dance music – all held longer than would be thought possible in order to build suspense. The vividness of the dramatization echoed the real-life newscasts whose bulletins so frequently concerned events ominously gathering in Europe. But whether Houseman or Welles intended any serious parallel is debatable: they just wanted to liven up the story, using what was going on all around them, on the air and in the papers.

So why did listeners think there was a real invasion from Mars being reported? Houseman attributed it to a chance circumstance. Broadcasting on another wavelength was the hugely popular Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy Show.

At twelve minutes past eight the improbable principal act – a ventriloquist and his assorted dummies – took a break, and so did listeners. They reached for their dials, surfed the frequencies, and happened upon a news report, well under way, of the Martian invasion. As the play progressed so did the hysteria.

An estimate for the number of American families who had radios at the time was twenty seven-and-a-half million. The radio was frequently the principal, and often the only, source of information for Americans about the wider world. And in those days listeners trusted unquestioningly that what they heard was the truth. Despite announcements that this was a dramatization of a book, people took to the streets, screaming that it was the end of the world.

There are many colorful stories of that night. Here’s one of them. In Staten Island, Connie Casamissina was about to get married. Latecomers to the reception took the microphone from the singing waiter and announced the invasion. As Connie recalled: “Everyone ran to get their coats. I took the microphone and started to cry – Please don’t spoil my wedding-day! – and then my husband started singing hymns, and I decided I was going to dance the Charleston. And I did, for 15 minutes straight. I did every step there is in the Charleston.”

After the program went off the air, terrified listeners who’d called CBS angrily threatened violence against Welles and the company, after discovering they were victims of what they thought had been a malicious hoax. One employee recalled: “Someone had called threatening to blow up the CBS building, so we called the police and hid in the ladies’ room on the studio floor.”

The fallout from the broadcast was extensive. How would the populace have reacted in the event of a real air raid?

There were calls for censorship, but freedom of speech on the airwaves was fiercely defended. In a striking piece in the New York Tribune, columnist Dorothy Thompson acclaimed the broadcast as “one of the most fascinating and important events of all time… It is the story of the century… Far from blaming Mr. Orson Welles, he ought to be given a Congressional medal and a national prize for having made the most amazing and important of contributions to the social sciences… He made the scare to end all scares, the menace to end menaces, the unreason to end unreason, the perfect demonstration that the menace is not from Mars but from the theatrical demagogues.”

Danish edition

As for Orson, he made a chastened appearance in a newsreel, adopting the air of a schoolboy who’s not sure whether he’s gotten away with a prank.

Welles at press conference after the broadcast

He wasn’t as worried about society’s judgment as he was about potentially more serious, legal penalties. In the end nothing stuck, and it all turned out to be one of the most fortuitous events of his career. But his personal creative responsibility for the show had been negligible, beyond the flair of his direction and performance. In a foreshadowing of his attempts to take credit away from Herman Mankiewicz for the script of Citizen Kane, Welles repeatedly attempted to deny Howard Koch’s authorship of War of the Worlds. Unsuccessfully, to his considerable annoyance.

There’s no evidence to support his contention that the program was planned as a Halloween prank all along. The idea was improvised on the spot as a sop to the panic released during the broadcast. Nor was there a conscious attempt to play on fears of a European invasion. The fact was that Welles barely thought about the program, being completely occupied until the last minute by his losing struggle with the theatre production of Danton’s Death.

However, he did get a Hollywood contract out of it.

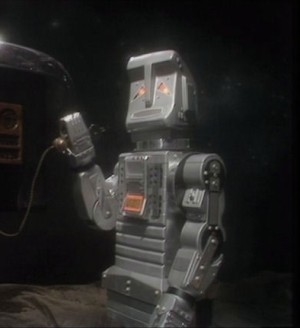

Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, at the site of the supposed Martian landing.