Where do gods live?

The people of the Himalayas believe the gods live in the high mountains, and that summits are sacred places. Everest was once known as Chomolungma, meaning “Goddess Mother of Mountains”. After the Chinese invaded Tibet their authorities decreed that the mountain would again be known by that name, rather than Everest (named after the surveyor who had first mapped the region for the British). Before leaving the summit in 1953, Tenzing buried some sweets and biscuits as an offering to the Buddhist gods of the mountain.

In 1951, as my father and other members of the Reconnaissance expedition gazed upon the southern slopes of Mt. Everest, did they wonder what gods they might encounter here?

As they peered into the lower reaches of the vast Western Cwm and up towards the towering Lhotse face, it was clear that whatever god or gods protected the mountain were going to make them work hard for the privilege of entering its Elysian snow fields. Mountaineers entering these high realms have been known to get a strong case of religion.

Not so my father. He was inclined towards practical thinking and was already well into his medical training when he first figured out a potential southern route to the summit in the basement of the Royal Geographical Society in 1951. The son of middle class expatriates living in Malaya, he had attended the public school of Marlborough, and therefore shared something of the gentleman’s club background of the British climbing establishment. However, he admitted to none of the sense of entitlement and rejection of professionalism that had plagued British mountaineering in particular, and British athletics in general, for years. (This issue was tellingly investigated in the Oscar-winning film about the British runners at the 1924 Olympic games, Chariots of Fire). The Alpine Club, home to generations of British climbers, was the Club of Clubs when it came to extolling the virtues of gung-ho amateurism over targeted training and systematic preparation.

My father was also well acquainted with Everest history, and the long series of British failures on the mountain. Already well into his training for an eventual career as a surgeon, he thought scientifically and methodically, and was determined to make sure none of the avoidable mistakes of the past would be repeated to keep the British from claiming their prize. Little did he know how much of an uphill struggle this would prove to be.

He knew about Mallory and Irving who, in 1924, had disappeared from sight en route to the summit.

He knew about the inadequate clothing, faulty equipment, bad hygiene, and the British abhorrence of taking anything more than an amateur approach to the laws of physics and anatomy during the course of preparations for Himalayan mountaineering. Reading the accounts by some of these Everest veterans one could be forgiven for thinking that it was better to martyr oneself on the mountain rather than admit scientific thinking into the climbing equation. “Muscular Christianity” was an ideology of embracing God through athleticism that came to prominence in the Victorian era and had become pervasive in the climbing world. Over the years Muscular Christianity had demanded — and received — a large volume of human sacrifice from its acolytes: toes and fingers from the frost-bitten limbs of those who survived, everything else from those who did not. Later in his career, my father became the go-to expert on frost-bite because of his success with preventing amputation.

The Everest problem, for my father, was the problem of high altitude – in particular the last thousand feet, where the human body enters a realm it is not naturally equipped to survive.

Here the air is so thin and cold, that, without supplementary oxygen, the human body starts to shut down, even though the owner keeps walking. Trouble was, no one had been able to lick the oxygen problem. Flawed thinking and faulty equipment meant more often than not that oxygen sets appeared to make things worse and were abandoned by frustrated climbers who often felt they intruded on the “pure” mountaineering experience anyway. Thus, as he approached the summit, the living climber turned into the walking dead. He just didn’t know it yet. The history of high altitude climbing is littered with tales of those returning victorious or otherwise from the upper reaches of the mountain only to die as they descend: literally stopped dead in their tracks.

My father spent his whole career railing against those who resisted the so-called “cheat” of having safety oxygen available at all high camps. Several superb mountaineers he had climbed with died needlessly on other people’s expeditions, he felt, because they did not have back-up oxygen for emergencies. Alan Rouse, who had climbed with him on the first ascent of Mt. Kongur in China, died on K2, sitting in his tent, left behind by his companions, drowning in his own bodily fluids as he spoke to his pregnant girl-friend by radio.

My dad felt events like these turned mountaineering into a blood sport, and his disdain for its practitioners knew no bounds.

For my father in 1951, the solution to the Everest problem lay not in faith – faith in the human spirit’s ability to endure beyond what was endurable simply through brute physical force and mystical will-power – but in a thoughtful, well-researched and practical application of scientific principles to the challenges of high altitude, cold, and the limitations of the human body to function in both. The question was: how to overcome these challenges, and who was the man to lead the way?

After he had figured out the route and approached the Himalayan Committee about putting together a Reconnaissance expedition, he made inquiries which led him to the name of Griffith Pugh. Thus it was that my father found himself walking into the gaunt edifice that was the Medical Research Council’s Division of Human Physiology in Hampstead.

In Harriet Tuckey’s probing new biography of Pugh, Everest – The First Ascent (whose revelations amount to a re-writing of accepted Everest history), she describes their fateful first meeting. It’s an iconic scene, straight out of a movie. After finding no receptionist at the front door, “Ward searched along wide, dark corridors, eventually finding Pugh’s laboratory on the second floor. Entering the laboratory past crowded shelves of scientific equipment, Ward was confronted with a large, white Victorian enamel bath in the middle of the room, full to the brim with water and floating ice-cubes. In the bath lay a semi-naked man whose body, chalk-white with cold, was covered in wires attached to various instruments. His blazing, red hair contrasted sharply with the ghostly white pallor of his face. The phantom figure was Dr. Griffith Pugh undertaking an experiment into hypothermia. Ward had arrived at the crisis point when rigid and paralysed by cold, the physiologist had to be rescued from the bath by his own technician. Ward stepped forward to help pull him out of the freezing water. So began a long, fruitful collaboration and friendship.”

Pugh, a brilliant physiologist, Olympic skier, and trainer of high-altitude commandos during the war, not only knew his science but also thought outside the box. Eventually he would reassess every aspect of equipment, diet, hygiene, and physical training in order to overcome the problems of “the last thousand feet of Everest”. In effect, the successful outcome of the ’53 expedition would have been impossible without this application of scientific thinking to an intractable series of problems. Pugh’s work revolutionized all sports that took place in the mountains, and paved the way for a whole new field of scientific inquiry, what my father would refer to as “a cornucopia of science”.

Hilary and Tenzing en route to the summit of Everest, wearing the open circuit oxygen sets that Griff Pugh had diligently refined.

But in order to achieve this Pugh would have to win over not only resistant climbers, but also the entrenched, anti-science culture of the Himalayan Committee that was running the show. It was a struggle every bit as epic as the quest to ascend the world’s highest mountain, and the true story of what actually happened, and the full measure of Pugh’s contribution, was suppressed for many years by those in a position to do so. It is only with the publication of Harriet Tuckey’s book that this riveting story – which in fact is far more interesting and inspiring than the hitherto accepted orthodoxy — has been made public for the first time.

In these fascinating extracts from a scientific film that Pugh assembled with the aid of Tom Stobart (the official Everest cameraman) and George Lowe (who shot the high altitude sequences), we can see some of the issues he was tackling.

After his experiences on the Cho Oyu expedition in 1952, a dry-run for Everest itself, Pugh insisted on an extended period of acclimatisation for the team. The benefits were enormous.

Another major factor contributing to the success in ’53 was an increase in food and fluid intake, per Pugh’s recommendations. He made sure to pack each climber’s rucksack with favorite delicacies for consumption at high altitude, where appetites were normally depressed.

My father found working on the science of high altitude with Pugh utterly absorbing, and it stimulated an interest he was to pursue for the rest of his life. Here he assists Pugh with a step-test in an experiment at Advanced Base Camp (21,000 ft.), just above the icefall.

My father’s interest in the effects of high altitude dovetailed perfectly with his career as a clinician and surgeon. When Pugh decided to put together the first dedicated expedition to research high altitude physiology, my father immediately came on board.

The Silver Hut expedition of 1960/61, in which a group of mountaineer-researchers lived at 19,000 feet for six months, performing a wide range of experiments upon themselves, jump-started a whole new field of research in spectacular fashion.

Riding a stationary bike inside the Silver Hut. My father would later continue these experiments high on the Makalu Col.

The constant round of experiments was alleviated by skiing —

— and by the ascent of local unclimbed peaks.

Ward and Gill, barely visible dots just below the summit of Rakpa Peak (named after the Silver Hut mascot).

My dad led a successful first ascent of the spectacular “Matterhorn of the Himalayas”, Ama Dablam, narrowly avoiding disaster on the way down when a sherpa broke his leg and had to be carried down on the backs of others, and sometimes swung like a pendulum off the peak’s precipitous rock faces. It was the first ever winter ascent, alpine-style, of a Himalayan peak; it was another eighteen years before the mountain would be climbed again.

The second attempted ascent of the expedition, of Makalu (the world’s fifth highest peak at 27,825 ft.), did not have such a happy outcome. Bad weather plus a series of accidents and collapses owing to high altitude resulted in the entire party being stranded at different camps high on the mountain.

If it hadn’t been for the presence of safety oxygen and the determined good sense of the one relatively inexperienced mountaineer in the party, John West, who climbed back up the mountain to see where everyone was, many could have died, including my father. He described his own rescue, after being stranded alone at 24,000 ft. for two days, thus: “At about 11 o’clock that morning I had my first brush with consciousness again. This was John West’s bearded face gazing at me. I remembered his teeth very well. They looked remarkably clean.” (The whole enterprise is described vividly in Harriet Tuckey’s book and my father’s autobiography, In This Short Span).

Members of the Silver Hut team: (l. to r.) John West, Mike Gill, Griff Pugh, Michael Ward, Jim Milledge.

The work at the Silver Hut led ultimately to my father writing the first wide-ranging text book in the field of high altitude medicine and physiology, and subsequent editions were co-written with two other members of the team: Jim Milledge and John West. Jim gave a most moving, and entertaining, address at my father’s funeral.

However, up to his death, my father, like Griffith Pugh, continued to suffer the scorn and cold shoulder of the leader of the ’53 expedition, John Hunt, and his acolytes. There were many reasons for this. As Medical Officer my father had to order Hunt to go down the mountain when he felt his deteriorating condition and insistence on “leading from the front” during the perilous ascent of the Lhotse Face was endangering not only the expedition but also lives.

There was also a heated confrontation over Hunt’s tactics for the final assault, in particular his choices concerning the setting up of high camps for the summit attempts. My father felt Hunt was compromising the chances for success of the first assault party of Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans by establishing their final camp too far from the summit. His misgivings were proved correct when the climbers had to turn back within sight of the top. Problems with their closed-circuit oxygen equipment, untested at high altitude, had delayed their progress. Pugh had warned Hunt this was likely to happen with the closed-circuit sets, which were a newer, more complex technology than the open-circuit design which Hilary and Tenzing, the second summit party, were to use. The controversy over Hunt’s strategy remains unresolved.

Here is Pugh’s discussion of the closed-circuit oxygen sets used during the first assault on the summit:

Hunt was a military man, and a fine leader in many ways (though not as strong a climber as the rest of the team), but he was definitely of the “Muscular Christianity” school of mountaineering. Harriet Tuckey: “He told his wife that on Everest he had carried with him a feeling that the hand of God was guiding him towards his goal. This sense of being chosen by God coloured the way he framed the official history of the expedition.” Which meant that science was largely relegated to the appendices of the official expedition book written by Hunt, and when mentioned at all in the official film of the expedition, made to seem like part of his own inspired leadership. There was barely a word of attribution for Griffith Pugh, the true architect of the boots Hunt had walked in, the clothes Hunt had worn, the food Hunt had eaten, the tents Hunt had slept in, and the smoothly functioning oxygen sets that had saved Hunt’s life on the Lhotse face and lifted Hillary and Tenzing to the summit.

In the introduction to the new edition of my father’s book, Everest: A Thousand Years of Exploration, the distinguished French mountaineer Eric Vola does not mince words in his appraisal of Hunt and his animosity towards my father.

He recounts an extraordinary episode which took place in 1973, at the 20th Anniversary Celebration at the Royal Geographical Society when my father spoke about the contribution of science to the success of the expedition. Afterwards Hunt came up to him, furious, and started shouting: “No one wants to hear about that science!”

Faced with the ironic silence of my dad (ah, how well I remember the futility of arguing with those silences), who was by then a distinguished senior Consultant Surgeon, Hunt became apoplectic: “I hate scientists”, he fulminated. Then he turned to another member of the expedition and said: “Someone should shut Ward up”.

The Everest team in Snowdonia: my father stands to the left of the group; Hunt, in black sweater, is in the middle.

At home my father remained remarkably sanguine about all of this. His greatest frustrations derived from having various expeditions to remote corners of Asia cancelled at the last minute because of local political instabilities, and having to deal with the officious bureaucrats of the National Health Service and their equivalents in the unions. On one memorable occasion, when the umpteenth strike closed down his operating room, he called up a fleet of taxis to pick up his patients and drive them through the picket lines to another hospital so he could continue his scheduled operations without interruption.

He was a dedicated believer in socialized medicine to the end, eschewed private practice (not for him the cultivation of an unguent bedside manner), and during his very active tenure as Master of the Apothecaries (the City of London’s oldest Guild) he implemented a number of forward-thinking programs in international medical co-operation. Foremost amongst these involved bringing his own specialized knowledge and experience to bear on the problems of medical relief after natural disasters in Third World countries.

His retirement from clinical work also saw a focusing on his many scholarly areas of interest, with articles being published in leading medical and mountaineering journals on a regular basis. Even a horrendous car accident in no way dulled his mind, which seemed ever ready for adventure. After completing his seminal Everest history, he turned to consolidating his lifelong interest and research into the extraordinary accomplishments of the pundits, native surveyors who mapped vast tracts of Central Asia for the British in secret, using the most basic tools and formidable memory. He had in fact learned these techniques himself, applying them in part on the Everest Reconnaissance of 1951, and more thoroughly during his trips to Bhutan in 1964 and ’65. (He used to practice being a pundit during walks in London’s Richmond Park — apparently much to my bewilderment as a toddler). A book was to be forthcoming, but his death curtailed the project until it was taken on by Richard Sale. The resulting volume, Mapping the Himalayas: Michael Ward and the Pundit Legacy, opens yet another window into his lifetime’s journey of exploration and scientific inquiry.

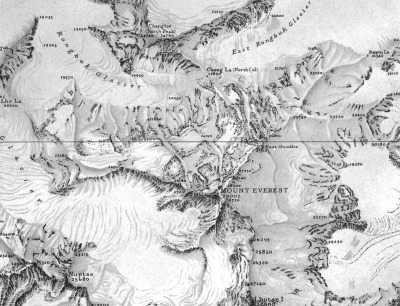

A page from my father’s 1951 Everest Reconnaissance diary, depicting the approach to the Western Cwm.

Looking at reproductions of pages from his Everest and Bhutan diaries enables one to share some of the same excitement he must have felt as he navigated through the icefall or looked upon the remote Lunana region, Bhutan’s own Shangri-La. He somehow always managed to be amongst the first Westerners to see these wonders.

Given the history of his fractured relationship with the Hunt establishment in British mountaineering, it was all the more striking – and gratifying – that when my father died the fulsome obituaries went out of their way to give him the full credit denied him in his lifetime for the many areas of pioneering work he brought to the worlds of mountaineering, exploration and high altitude medicine. I was stunned to see The New York Times give him equal space with the legendary civil rights activist Rosa Parks. These were two indomitable characters who I think would have liked each other if they had met.

His funeral was remarkable for its celebratory nature, and revelatory in a way that he would have been profoundly moved by. Several elderly gentlemen, who had traveled long distances to attend, were amongst the congregation in the packed church, and were unknown to both myself and my mother. It turned out that they had been medical students under my father’s tutelage. He had inspired in them equal parts terror of what would happen to them if they made a mistake or forgot some obscure fact, and complete devotion to the practice of good medicine. That he had so inculcated in them the spirit of excellence, intellectual honesty, and moral integrity was a legacy he would have been proud of above all others.

The approach to Mt. Kongur in China (climbed by my father’s expedition in 1981), seen across Lake Karakul.

To me, personally, he was a remote figure in many ways, the result of his own emotionally undernourished childhood. It was therefore a treat to see him bond so completely with my daughter, who, upon meeting him for the first time, declared that he was “Dodo”. He wore his new name like a badge of honor. My greatest regret is that I didn’t sit down with him, with a tape recorder, and just talk. Get all the stories. All the knowledge. All his insights into a time when true explorers roamed the earth and walked off the map and had adventures the rest of us can only dream of.

He was a daunting figure in his accomplishments and no-nonsense disposition. His competitive streak, combined with a disregard for the niceties, could make him seem brusque, somewhat remote. But, in truth, he was a man of deep feeling: a remarkable man from a remarkable generation of men who, like the great British film director David Lean, were always looking to the far horizon, then tried to figure out the most interesting way of getting there.

This is the third and final part of my reminiscences about my father’s role in the First Ascent of Everest and the 1951 Reconnaissance Expedition. You can read Part 1 – “Watching Dad on Everest” here, and Part 2 – “My Dad, the Yeti, and Me” here.