One of the perks of having my dad for a dad was the strain of unusual and exotic experiences that ran through my life as a result of being related to a Himalayan explorer, one of the team that first climbed Mt. Everest in 1953. For example, aged 6, having tea with the Queen of Bhutan and her family in a Kensington apartment, while a bodyguard named Rinzi, wielding a substantial saber and sidearm, stood guard nearby. (He was forever memorialized when I gave my childhood spaniel the same name: they shared a disposition of attentive watchfulness and deep brown eyes. And how many other London kids could say their faithful hound was named after a royal Bhutanese bodyguard? Thanks, Dad.)

One of the perks of having my dad for a dad was the strain of unusual and exotic experiences that ran through my life as a result of being related to a Himalayan explorer, one of the team that first climbed Mt. Everest in 1953. For example, aged 6, having tea with the Queen of Bhutan and her family in a Kensington apartment, while a bodyguard named Rinzi, wielding a substantial saber and sidearm, stood guard nearby. (He was forever memorialized when I gave my childhood spaniel the same name: they shared a disposition of attentive watchfulness and deep brown eyes. And how many other London kids could say their faithful hound was named after a royal Bhutanese bodyguard? Thanks, Dad.)

When friends came down to the country for the weekend, we’d haul out my dad’s tent and camping gear. “What’s that smell?” my chums would ask, noses pinched.

“Yak!” I would respond with glee. God knows what ingredients actually created this odor. This stuff had been perched for a winter at 19,000 feet near Everest. Or was it a leftover from those epic treks through Bhutan, going to places no Westerner had ever been, venturing into terrain more Shangri-la than Shangri-la? No matter. The smell, though pungent, evoked Adventure with a capital ‘A’.

But the story which I got by far the most mileage from, and still do, is of the time my father encountered serious evidence of that legendary hobo of the Himalayas: the yeti, or abominable snowman.

“Oh come on, you’re pulling my leg,” any companion whose ear I am bending with this tale will protest.

I whisk out my phone and google ‘yeti footprints’. “There are photographs to prove it,” I declare, almost offended by the lack of faith.

“Those photos? Those are your dad’s photos?”

I nod my head, “Yup, next to the footprint that’s his boot”.

“Cool!”

Very.

Thanks again, Dad.

This is what happened.

Fall 1951, and the Everest Reconnaissance party had been making its way laboriously through the Khumbu icefall, tricky and dangerous work, trying to reach the Western Cwm. From there they could better see where a possible route to the summit may lie. My father writes in ‘Everest: One Thousand Years of Exploration’: “Towers of fragile ice fell without warning and crevasses continually opened and closed. The icefall had become an immense, unstable ruin, as though an earthquake had shaken the entire glacier.”

Various routes through the upper reaches of the icefall were attempted, then abandoned. Finally, a few days later, they broke through into the Western Cwm, only to be confronted by an immensely wide and deep crevasse which barred the entrance to the level valley of deep snow beyond.

“I started down one or two places where we thought it might just be possible to descend to the bottom of the snow-choked crevasses many feet below; but even if we could have reached these ‘bridges’, they might have collapsed, or we might have found that the near-vertical ice on the far side needed artificial climbing and the use of our small stock of suitable hardware….

“Eventually we gave up. I felt very frustrated by this decision, for here was a good piece of technical climbing which, as I was getting fitter, I would have liked to try…. But, as Bill Murray put it: ‘We had climbed up and we had climbed down the impossible! Gainsaying the pundits we had found a route up Everest. This route would go.’”

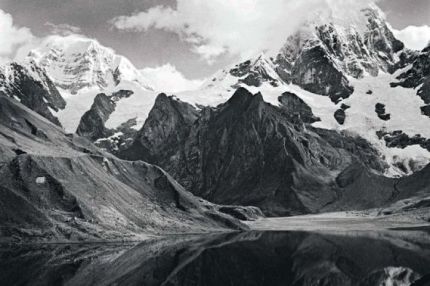

The main work done, the team split up into different groups to explore some of the surrounding country. My father, together with Eric Shipton and Sherpa Sen Tensing set off towards an unknown peak, “a glorious spire of pale pink granite, capped by snow.”

They named it ‘Menlungtse’, “after the stream that meandered through green meadows around its foot – a vast amphitheatre of pastureland glacier.

“For our crossing of the Menlung La, we were traveling together, unroped, at about 16-17,000 ft. It was at about midday that we came across some tracks on the snow of the glacier. Sen Tensing had no doubt in his mind as to what they were – yeti tracks. Questioned closely, he was quite adamant that he had seen similar tracks in Tibet and other parts of the Himalaya. Here there seemed to be two distinct sorts of track. One was well-defined in that individual prints had recognizable features such as toes; a second group was less well defined, with few if any individual features.

“The more interesting were the well-defined tracks, most of which were on a thin covering of snow over hard glacier snow-ice. Many, but not all, of the imprints were clear-cut, and there were a great many of them.”

They paused, chose one especially clear footprint, and took photos.

“These distinct tracks went down the glacier and we followed them for about half an hour before they turned off into a side moraine; we continued down the valley. The tracks went straight down the glacier, which was almost level but with some very narrow and shallow crevasses, perhaps about a foot or less wide. Where those crevasses had been crossed by a line of prints, it seemed as if a ‘claw’ had protruded beyond the imprint of each of the toes.

“About 48 hours later, Bourdillon and Murray followed the line of the yeti tracks further down the glacier, and both men noted in their diaries that, though deformed by wind and sun, the tracks took an excellent line down the glacier.”

Clearly whatever creature had made the tracks was every bit as good a navigator of high mountainous terrain as British climbers!

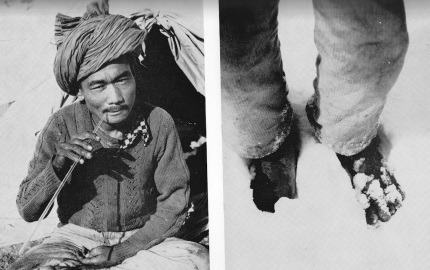

When released to the public, the photos, naturally, caused a sensation. They remain the one clear piece of photographic evidence for the yeti that is not easily explained away. Forever after, my father was plagued with accusations that he and Shipton had somehow “made up” the footprints as a practical joke, a possibility belied by the independent corroboration by the other two climbers.

Lacking any other definitive evidence for the yeti, my father’s own best theory for the cause of the footprints was a human: “Though neither Shipton nor I realized it at the time, the inhabitants of the Himalaya and Tibet can and do walk in the snow for long periods in bare feet without frostbite, and I was later to see this also in Bhutan and Tibet… “

He wrote papers on the subject for the Alpine Journal and Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, detailing a number of conditions that could result in enlarged toes and even deformities of the whole foot.

“The ‘claw marks’ observed in the Menlung prints could be explained by the presence of Onychogriffosis or ram’s horn nail…

In January 1961, during the Silver Hut expedition in the Everest region, a Nepalese pilgrim who normally lived at 6,000 ft. visited our research sites and lived for fourteen days at 15,300 ft. and above. Throughout this period he wore neither shoes nor gloves and walked in the snow and on rocks in bare feet with no evidence of frostbite. Moreover, he slept outside with no shelter, at measured temperatures of minus 13ºC, and managed to avoid hypothermia by controlled light shivering.”

What do I think? “There are more things in heaven and earth…” A few years ago an ABC News team was in the Everest region and came across yeti footprints. They were on the same glacier where my father and Eric Shipton had been in 1951.

Back on Everest, more drama was to follow. After a few days my father and his companions realized they had strayed into Chinese-occupied Tibet, a dangerous situation that could end up provoking an international diplomatic incident if they were discovered. It could imperil the whole Everest adventure. They decided to make a run for it at night, along the banks of the river that raged through the Rongshar gorge. This was the stuff of the adventure stories and movies my dad lapped up as a kid, but it was all somewhat more alarming when you found yourself actually in one for real.

“The thunder of the torrent beside the path reverberated against the canyon walls, drowning the noise of our footsteps as we passed quickly through Topte village, hoping that the Tibetan mastiffs, let off their chains at night, would not hear or smell us. In the dark we stumbled over roots and rocks – in places a tree ladder had to be climbed, and in one fearsome place the path was only a few branches wide, balanced on a cliff face thirty feet above the boiling river and held onto cracks in the rock by small twigs.

“At about 4am our ‘smuggling’ sherpas reckoned we were past the frontier and we stopped and slept at the side of the path. An hour later the sun came up and we were surprised by a group of six wild-looking Tibetans with long pigtails, armed with swords and muzzle-loaders with antelope-horn rests, who erupted into the scene with much shouting. We could not escape since a vertical rock cliff of over 2,000 ft. towered behind us, and the boiling Rongshar river was only a few feet away. Immediately a noisy and furious argument started, with much gesticulating and shouting. Angtharkay (the head sherpa), all of five feet tall, seemed incandescent with fury. As the whole argument was conducted in Tibetan, we had no idea what it was about.

“After ten minutes of this Angtharkay came over to us and suggested that we four Europeans should retire a suitable distance away while he and the other Sherpas sort things out. After a further twenty minutes he returned with a broad grin. ‘Everything is settled,’ he said, ‘but I am afraid it will cost you seven rupees to buy them off.’ Ten rupees had been demanded, but Angtharkay had considered this exorbitant. The shouting had been the negotiations.”

All returned safely to England, and a new route to climb Everest had been found.

My father was never one to spontaneously break into tales of his exploits, but when I could coax him to speak about his various adventures (and Everest 1951 and ‘53 were only the first of many), his eyes would light up as, in his mind’s eye, he would step back into his climbing boots and walk into these stunning landscapes, unmapped regions of the earth that he was amongst the first westerners to explore.

I recall, aged around 9 or 10, venturing with him into the Harrods bookstore and discovering for the first time the Tintin series of original graphic novels. I scanned the brightly illustrated covers which promised exciting adventures underseas, in the jungle, on a crashed asteroid, and even in space. Where to begin?

My father spoke: “Well, you’re going to have to pick one of them.”

Then my eye fell upon the only possible choice:

The cover scene was eerily similar to the one my father had lived through in real life.

I beamed as I handed the book to the cashier.

“My dad met a yeti once,” I proudly announced as she rang me up.

The cashier smiled indulgently at me and then my dad: “Oh really, how interesting.”

My father, with the smallest hint of a grin, handed over his money and said not a word.

Footnote: First serialized in 1958, Tintin in Tibet was Herge’s personal favorite among his many tales of the young reporter, and was no doubt influenced by my father’s well-publicized yeti photos, as well as by the author’s own fascination with the mysticism of Tibetan Buddhism. He wrote it as a personal journey of redemption during a period of crisis, when he was assailed by recurring nightmares of “the beauty and cruelty of white”. His Jungian psychoanalyst told him he needed to destroy “the white demon of purity” in his mind. One imagines that some climbers who have come near to death as they pursue their passion for ascending into the highest realms of the earth are well acquainted with “the beauty and cruelty of white.”

This is Part 2 of my reminiscences about my father’s role in the First Ascent of Everest and 1951 Everest Reconnaissance. You can read Part 1 – “Watching Dad on Everest” here, and Part 3 – “My Dad on Everest and Beyond”, here.

Pingback: MY DAD ON EVEREST AND BEYOND ( OF GOD AND SCIENCE ) | HOLLYWOOD ( and all that )

Pingback: WATCHING DAD ON EVEREST ( THE FIRST ASCENT AND 1951 RECONNAISSANCE ) | HOLLYWOOD ( and all that )