To transfigure: to transform into something more beautiful or elevated

There are experiences in all our lives that so completely transcend the mundane that we step out of time completely. Those experiences live on in the eternal present in our heads and we are, on some deep molecular level, altered by them – utterly.

I had one such experience recently. I was not the sole participant in the event that prompts these words. But I dare say many of the 300-plus performers who shared the stage with me at UCLA’s Royce Hall felt similarly. We were there for two reasons. First to perform two of Beethoven’s great choral works, the Mass in C and the Choral Fantasy. Second, to mark and celebrate the extraordinary musical life of our conductor and choirmaster, Donald Neuen, Distinguished Professor of Choral Music at UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music.

At the age of 80, after a sixty-year career of conducting and teaching, Donald was retiring. Yes, that white-haired gentleman on the podium summoning up a veritable tempest of musical joy was less a Prospero thinking of lazy afternoons in a more temperate clime, than a newly liberated Ariel, ready to take on the world with mischief to spare.

There are those people who feed on life and give nothing in return, who drain the colors from the canvas. Then there are those who accept nothing as enough, who believe everything is possible, and who view adversity as opportunity. Opportunity to strive, to create, to enrich, to find the Yes buried within the No. Beethoven was one such man, and Donald Neuen is another. When these two finally meet, it won’t be over sedate scones and Earl Grey at the Elysian Tea Rooms. There will be no talk of what was and what could have been. No Falstaffian reminiscences of “the days we have seen”. More likely the conversation will go something like this:

Neuen: “So, been working on anything new?”

Beethoven: “Yes. But it’s really difficult. I doubt you can find a choir capable of singing it.”

Neuen: “Then I’ll make one.” (Turning to the hovering angels): “Now who among you can actually sing?”

It seems as if Beethoven, like music, has always been a part of my life. As a toddler I figured out how to operate my father’s old portable record-player with precocious alacrity, and, along with Holst’s Planets and Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, Beethoven’s symphonies were rarely far from the spinning turntable. The hammer blows of the 5th, the frenzied dance of the 7th, and the soaring finale of the 9th were the soundtrack to my precocity. The Sixth Symphony, nicknamed the Pastoral for its musical depiction of walks in the countryside, bucolic peasant scenes and thunderstorms, remains my go-to piece for spiritual solace. It’s music that puts what really matters in life into perspective, that says: “This is you, and this is your place in the cosmos. Treasure the world around you and it will bring you enlightenment.”

It’s a truth we still find hard to live by.

Beethoven was at odds with the world, and his music reflects his Promethean spirit with a naked, and sometimes painful, honesty. He accepts nothing, wants everything, and rails against the gods when he has to settle for something less than the ideal – which is most of the time. His deafness, the cruelest of cruel jokes to ever befall a composer, would have felled most musicians; instead it emboldened Beethoven. When you can no longer hear the sounds of this present world, you imagine the sonorities of worlds to come. And so it was with Beethoven: his music grasps for a future he desperately wants not only to hear, but also to live. His notebooks testify to his struggle to find the language – the notes – to encapsulate those sounds, that vision.

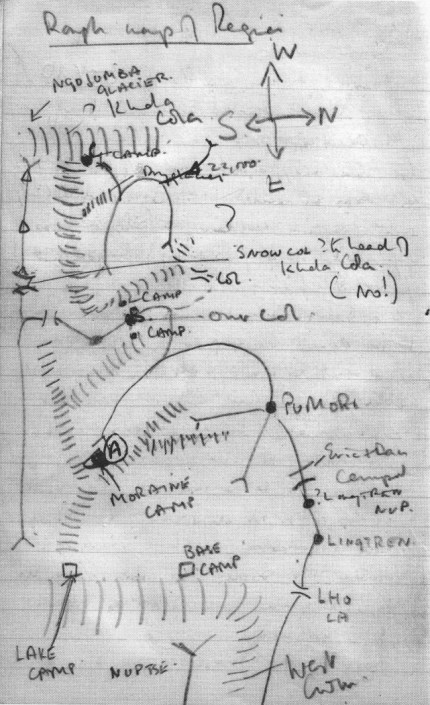

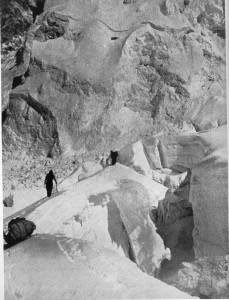

One of Beethoven’s sketchbooks, containing material for the Missa Solemnis. This was once owned by Mendelssohn.

Musical ideas erupt messily from the pages, some scratched out in a fervor of second and third thoughts. The masterpieces in his portfolio are legion, spread across all musical genres of the time. They articulate a humanist, inclusive, utopian vision, brought about as much through music as through political and ideological reformation. This vision finds its fullest public expression in the end of Fidelio and the Ode to Joy from the 9th Symphony. The more interior reckoning is to be found in the late piano sonatas and quartets.

By some miracle of happenstance (or the benign influence of a god who loves music), Beethoven lived at the precise moment in time when musical language could, for the first time, sufficiently encompass his Dionysian impulses within an Apollonian frame. This was during the maturation of the so-called Classical period, articulated and embodied by Haydn and Mozart. Harmonic language found itself at a point of complete equilibrium between concord and discord. Tonality was held in balance, yet to succumb to the unraveling by the late Romantics that resulted in dodecaphony at the turn of the 19th century: the equalizing of all harmonic impulses, be they concordant or discordant – the democratizing of dissonance. As music plunged towards the maelstrom of the 20th century it moved towards a liberation from any sense of a tonal center in the music of Wagner, Richard Strauss, and early Schoenberg. From here it was but a small step to the convulsions of Stravinsky, Bartok and the birth of serialism.

In the Classical period (roughly 1730 to 1820), rhythm had become sufficiently liberated to both disrupt and also assert order. Beethoven was too wayward and forward-thinking a spirit for the more formal structures of the Baroque, and in the 20th century the freedom to do anything tonally and rhythmically would have overly diluted the tension between disruption and resolution (or, perhaps more accurately, containment) that drives his musical dialectic.

Sonata form – the principal means by which musical material was organized at the time – was the cornerstone of the Classical era in which he composed. It had just enough elasticity to allow him to push his ideas to the limit without breaking the vessel. You see hear this over and over again, but never more tellingly so than in the famous passage in the development section of the Eroica Symphony’s first movement, where a series of hammer blows in the form of dissonant chords threatens to upend the entire harmonic and rhythmic structure. But just when you think the musical vessel is going to buckle and break completely, Beethoven pulls back so that the music’s natural order can reassert itself. (Almost a century later, Stravinsky, working with the same kind of hammer-blow motif in The Rite of Spring, is only too happy to splinter the vessel asunder and ride headlong into the whirlwind.)

These kinds of musicological preoccupations take on a different hue when one actually has to perform Beethoven’s music. In his own lifetime, the impulse behind the music – its deeper intent and modes of expression – reached beyond the notes written on the page to a degree that musicians and listeners found difficult to wrap their heads around. Even the instruments themselves seemed inadequate. The so-called Hammerklavier sonata for solo piano, which did, literally, hammer in a manner designed to cripple, it seemed, the instrument’s mechanism, was merely the first volley of an all-out assault on the piano’s physical capabilities. Beethoven’s music was a major factor in the instrument’s evolution away from Haydn’s polite parlor-room fortepiano into the über-instrument of today: the 9-foot long Steinway Grand used in today’s concert halls.

Controversy still rages over the precise meanings of Beethoven’s seemingly contradictory (and often willfully impossible-to-play) metronome markings (the score’s indication of what speed the music should be taken at). These issues have still not been entirely resolved by the most recent, scholarly editions of his works by Jonathan del Mar, as witness the frequency with which his recommendations are ignored by conductors. (Though this might be more accounted for by the extent to which interpreters, especially conductors, feel a right – indeed a need – to appropriate Beethoven for their own aesthetic agendas, and damn the textual niceties. Two recent examples of this inclination are Mikhael Pletnev and Christian Thielemann.)

Given the technical and interpretive challenges of Beethoven’s music, it was hardly surprising that at our first choir rehearsal for our concert, Professor Neuen began by addressing two core issues for anyone planning to sing Beethoven: vocal production and rhythm.

He talked about how Beethoven demanded an intensity of singing that, if one did not employ good technique, could literally tear one’s vocal chords. To avoid this he talked about how one must project more from one’s forehead than from one’s chest, and he carefully walked us through the way to achieve this (complete with diagrams). Allied to this was an idea we had to firmly implant in our brains of sending forth our voices from our bodies in a cone – an almost literal, physical projection of sound. (This also came with a diagram). By the time of our concert, seven weeks later, that “cone of sound” would be hitting the audience like a physical force, a literal “wall of sound”, even when we were singing pianissimo.

At some point in the midst of the rehearsal process, when our singing was occasionally lacking a certain focus and power, Professor Neuen pulled out a book about the great choral conductor, Robert Shaw, with whom he had trained and worked, and whose approach to choir training he had absorbed and emulated.

He read us a quote from Shaw:

“People, the flesh must not be weak. Beethoven is not precious, he’s prodigal as hell. He tramples all over nicety. He’s ugly, heroic; he roars, he lusts after beauty, he rages after nobility. Be ye not temperate. Enter ye into his courts on horseback.”

This came from a letter Shaw had written to his choir, the New York Collegiate Chorale, as they prepared for a performance of Beethoven’s 9th under the baton of the legendary maestro, Arturo Toscanini. The letter continued:

“Which, being freely translated, means: Get your backs and your bellies into it. You can’t sing Beethoven from the neck up – you’ll bleed. Quit sitting back on your soft little laurels. Get your feet on the floor. Get elbow room. Spread your back. Keep your neck decently erect and your throat open. Don’t lead with your chin. And give with the part of your gut that ties onto your ribs. Make your body do part of the work. And, oh yes! Get lots of sleep. Read lots of good books. Drink lots of milk and orange juice. Think good clean thoughts. Love your neighbor – and Allah be praised.”

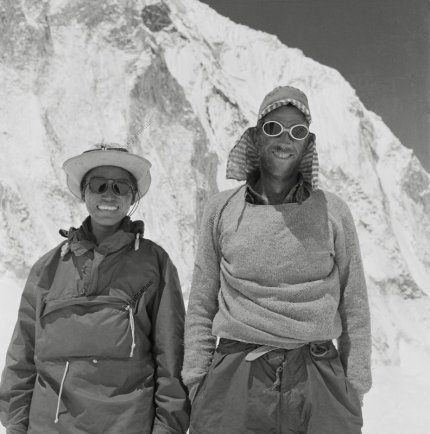

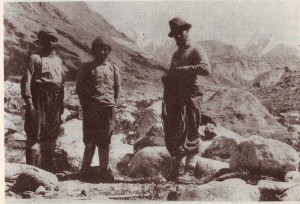

Robert Shaw conducting the New York Collegiate Chorale at opening of United Nations Building in 1953

This advice Donald recommended we follow too. I swear a look of quiet despair passed across the faces of those students inclined to dedicate the end of the school year to more Dionysian pursuits. Yet adhere to Donald’s dictum they needs must do: it was already clear he inspired fierce loyalty, devotion and love in his singers. This was all the more remarkable considering the majority of the choir consisted of non-music majors. The keg parties would have to wait.

As to rhythm, this is at the core of Beethovenian style. His music’s characteristic cut-and-thrust is achieved, in part, by accenting the offbeats and upbeats which, traditionally in music up to and including this period, are played more lightly, leading into the heavier downbeats. This off-the-beat accenting is so counter-intuitive, going against pretty much all the early training musicians receive, that Professor Neuen was reminding us of it right up to the dress rehearsal. With the orchestra in full flight, those lazy upbeats (KYR-i-E instead of the required Kyr-I-e) would cause him to yell “BEETHOVEN!!!!” and, somewhat shamefaced, we would make the necessary adjustment.

Thrilling as the concert was (and it was thrilling, like riding a bucking bronco on a high-wire over the Grand Canyon), it was the many weeks of rehearsal leading up to it that I treasure. Attending rehearsals was like embarking on a great journey with a companion from whom one never ceases learning. I had forgotten (as so many of us do once we leave school) what it is like to embark on a course of study in the company of a great teacher and inspirer of men. There is a sense of moving towards a place of enlightenment that the so-called “real world” of jobs, marriage and kids can seem to deliberately obfuscate.

Arrayed around Professor Neuen in rising semi-circular tiers, like the audience before the actors in a Greek amphitheatre, we were alternately coaxed, lulled, harangued, goaded, bullied, inspired, shamed and seduced into action by the kind of leadership that wins Superbowls and great battles. In fact, Neuen has been compared to the legendary coach of UCLA basketball, John Wooden, known as much for inspiring the hearts and minds of generations of student players as for capturing trophies. Neuen had, in fact, once contemplated a career in sports, that is until he became involved in choral training. Once he caught the choir bug there was no turning back.

But, as I rapidly learned, the strictly musical preparation that took place on Monday and Wednesday afternoons was only one part of the “Neuen experience”. In the midst of wrestling with half and quarter notes, recalcitrant tuning, listless rhythms and all the other ailments that afflict even the nimblest of choirs, the Professor would put down his baton, settle into the back of his stool and invite us to share a “sit-back” moment. There would follow a reminiscence, or an anecdote, or an observation of musical methodology or history, that would, first of all, be informative and helpful to what you were trying to achieve in the rehearsal room. But then you would start to realize there were other applications for these bon mots. They were little lessons to make you feel better about how your day was going, where your life was at the moment, and where it might go in the future. All those petty preoccupations and obsessions from outside the rehearsal room, the general life-malaise with which we so easily fill our daily internal monologue, would suddenly all reveal themselves as the utterly disposable bric-a-brac they truly were. From there it was but a small step to putting them all into a little box, placing them in a drawer, closing and locking it with the thought that you might revisit at a later date, but actually you also might not need to. Then it was “Back to Beethoven”!

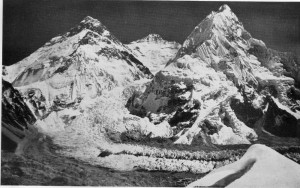

The concert hall at Eisenstadt where the Mass in C had its less-than-triumphant first performance. Prince Esterhazy II, who had commissioned the work, was none too happy, declaring: “But Beethoven, what have you done here?”

The Neuen “sit-back” moments, I learned, were famous, and rightly so. They were the lobs of a great champion on the tennis-court of the day’s preoccupations, bringing with them enlightenment and inspiration. They slowed down life’s driving forehands, jabs and seemingly insurmountable volleys and overheads. They changed the rhythm of the game, so that the defensive back foot play reset the balance of power. From love-forty down one could find oneself serving for the match.

And so, finally, and all too quickly, came the performance itself: the pomp and splendor of some 350 performers arrayed across the stage of one of the world’s great concert halls, UCLA’s Royce Hall.

It was here that the Decca recording label made many of its most celebrated recordings of the 60s and 70s, capturing the legendary acoustic and the sounds of the Los Angeles Philharmonic with its now classic array of “Decca tree” microphones.

Led by Dr. Rebecca Lord, who gained her PhD at UCLA under Neuen’s tutelage, and who had then become an Associate Professor in the Choral Department, there were speeches, tears – and even bugle volleys courtesy of fellow faculty member, Jens Lindemann, of the Canadian Brass.

(l. to. r) Jens Lindemann, CEA Vice President Stephanie Sybert, Dr. Rebecca Lord, Professor Donald Neuen, CEA President Kanwal Sumnani, and SPARK Coordinator Elizabeth Seger

Current and former pupils and singers who had been touched by the Neuen magic flew in from around the country. The house was packed for a concert whose costs were met by an online campaign organized by the students themselves.

But finally, ineffably, after the tributes and the farewells, there was the most important thing of all —

— the music.

Music by Beethoven!

As Professor Neuen strode towards the podium one last time for the Mass, he shook his fists like a great baseball hitter heading out to the plate in extra innings, bases loaded. Everything to win, everything to lose. He mouthed only one word: “Beethoven!” And we all knew exactly what work had to be done.

To participate in a great performance, led by a great conductor, is to reach so far beyond oneself that the process has the quality of a dream. Or, sometimes, a delirium. An articulate, controlled delirium, but a delirium nonetheless.

The notes are learned, everything is practiced and rehearsed to the nth degree, yet in the moment of performance the process is a both a frenzy and a becalming. Our minds are necessarily racing, because all music-making at this level is primarily about thinking hard and fast, always one step ahead of the score.

Our thoughts are driving our bodies to make the required sounds with constant changes in pitch, rhythm and expression. In the process we seem to become almost autonomous, divorced from ourselves, bound up into a collective, but also singular, act of creation.

The conductor’s baton, his eyes, his will, gather us up into a single thought. And in that thought, that moment, it seems as if the notes were never actually written down by the composer, the music never printed, never passed around, never scrutinized, studied, dissected and re-assembled, never worried over ad infinitum in the rehearsal room. The notes, the music, seem simply to emerge spontaneously in the here and now, drawn up from some distant consciousness we call Beethoven, to be hurled into the cosmos like the fire Prometheus stole from the gods.

With Beethoven one always seems to come back to the prodigious Prometheus; the composer even wrote music for a ballet about the mythical figure.

What, asks Man of his gods, is it for, this music? What does it mean?

Why, the gods answer, do you need to ask?

The music, and the making of the music, is its own answer.

And so, the orchestra plays, the soloists and choristers sing: “a lifetime”, as T.S.Eliot writes in Burnt Norton, “burning in every moment”.

The 80-year-old professor who has given his ideas, his passion and his grace to his students, friends, colleagues, family and the family of men and women who have shared his life’s journey; who has given his life to music, and the idea of music – that professor stands before us one final time on the stage. He invites us, through Beethoven, to reach out into the void, and pluck forth meaning.

As the conductor and choir trainer par excellence Robert Shaw once wrote:

“The Arts have a chance to become what the history of man has shown that they should be – the guide and impetus to human understanding, individual integrity, and the common good. They are not an opiate, an avoidance, or a barrier, but a unifying spirit and labor.

“The Arts are not simply skills: their concern is the intellectual, ethical and spiritual maturity of human life. And in a time when religious and political institutions may lose their visions of human dignity, they are the custodians of those values which most worthily define humanity, which most sensitively define divinity and, in fact, may prove to be the only workable Program of Conservation for the human race on the planet.”

And so, in Royce Hall, this extraordinary music that a deaf man wrestled into existence from the void, lives again – in our hearts and voices. In the process something deeper lives too. The Soul of Man.

The teacher and leader is young again —

— and we are old.

It is a complete and perfect metamorphosis, both within – and outside of – time.

As the music sounds, we are all, performers and listeners alike, translated –

— and transfigured.

You can watch the complete concert here: