I wouldn’t say it is the greatest movie ever made, but it is certainly one of the greatest moviegoing experiences you will ever have.

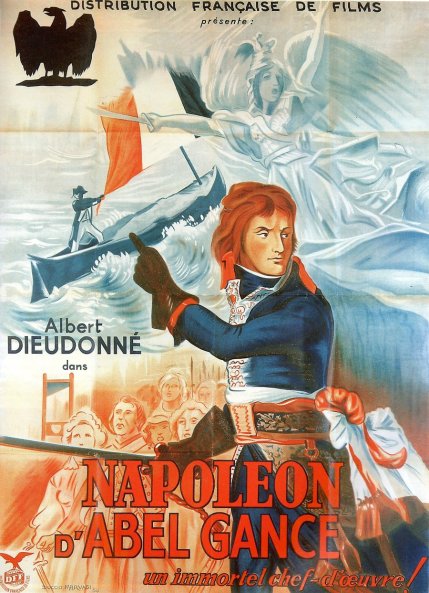

Audiences worldwide may have thrilled to the silent-movie charms of 2011’s Oscar-winner, The Artist, but Londoners are soon to have the chance to take the ultimate cinematic ride – and the ultimate trip into cinema’s haloed past. On November 30th the Royal Festival Hall plays host to a rare screening of 1927’s Napoleon, vu par Abel Gance in the most recent restoration by Oscar-winning film historian Kevin Brownlow. When this made its American début last year at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, the Los Angeles Times could merely exclaim, breathlessly: “Napoleon came. Napoleon was seen. Napoleon conquered.”

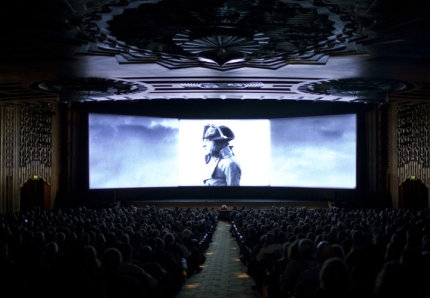

This was no mere hyperbole. I was there. Twice. And, even though I had been present at this restoration’s fabled first screening in London over thirty years ago, the screenings in Oakland’s Paramount Theater, a beautifully restored art-deco extravaganza, were in a class of their own. Just entering the lobby transported you into another world.

Then, as the film itself began, the 21st century receded, and for the next 5-1/2 hours one was was completely immersed in the world of the French Revolution, brought to life with a veracity, vigor and, conversely, modernity, that has yet to be matched. By the time the final triptych had unspooled my 15-year old daughter was rendered speechless with awe.

She made up for her uncharacteristic muteness by telling everyone during the following weeks she had seen the greatest film ever made. E-V-E-R.

And who amongst those who were there could argue with her? Napoleon is a complete one-off, a film sui generis. The apogee of the silent movie art. To see it under these optimal conditions is truly a once-in-a-lifetime event.

How could a modern, plugged-in teenager be so completely wowed by a nearly 90-year old silent picture?

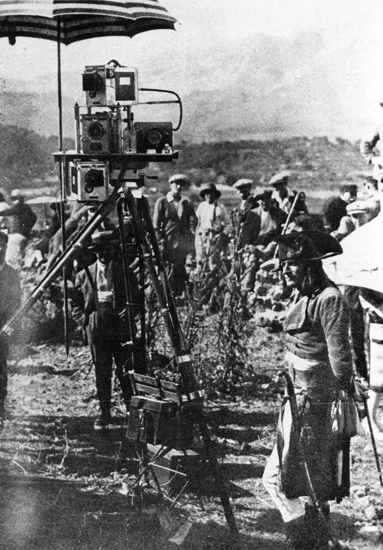

For starters, the film operates on a level of visual innovation and spectacle that today’s movies are still catching up with. (Gance even did tests for shooting some of it in 3D). Then there are those obsessively detailed sets and costumes which give the film an incredibly authentic feel and texture. Scenes in Corsica were shot in Napoleon’s actual family home on the island.

The performances range from grand to intimate, with a sense of commitment that is riveting.

Then there’s Carl Davis’s score, performed by a live orchestra, which forms a visceral conduit into both the period and the emotions of the drama. (Comparing it to the insipid score by Carmine Coppola, the only music Americans had heard during previous road shows of the restoration in this country, provides an object lesson in good and bad film scoring.)

The audience in London, like that in Oakland, will be seeing the most complete version of the film in existence, a restoration that has occupied Brownlow for a lifetime, funded by the British Film Institute and Photoplay Productions. It will be projected at the correct speed (making movement more naturalistic), and is hand tinted. Accompanying it will be that same original score composed and conducted by Carl Davis.

Over a period of more than four decades, Davis and Brownlow, together with producing partners Patrick Stanbury and David Gill (who died in 1997), have done more than anyone to bring silent films back from the grave of decaying film libraries, where 73% of films made before the coming of sound have crumbled into dust. Through a plethora of documentaries and live presentations in grand theatres with symphony orchestras, classics like Greed and Ben-Hur, as well as lesser-known gems like The Wind and The Chess Player, have all left viewers agog at the forgotten accomplishments of filmmakers of the silent era.

Napoleon, though, is the one to beat: a film whose ambition to redefine the art-form is evident in every frame. Originally intended to be six films covering Bonaparte’s entire life, in the end Gance blew his entire budget on Part One.

By the time of its première at the Paris Opéra in 1927 the film had already being cut down by its nervous producers.

In the succeeding decades the film was scattered across archives, private collections, and flea markets around the world.

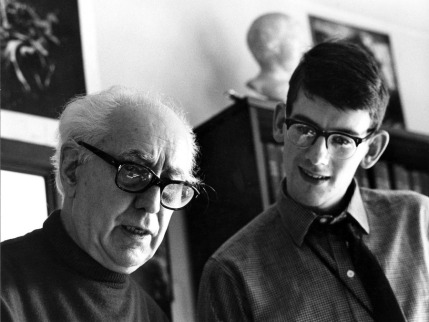

Gance himself never regained his full creative powers: a later, sound version of the film that incorporates some of the original footage has none of the original’s flair. By 1953, when the 15-year-old Kevin Brownlow, already an avid collector of silent films, screened fragments of a home-movie version in his makeshift home cinema, Gance and his film barely made the footnotes in movie histories. The story of Brownlow’s quest to restore the film, and Gance’s reputation, is one of those tales from the back rooms of film history that is as riveting as the film itself.

The film covers Napoleon’s childhood days at military school, the Revolution and his rise to power, his romance with Josephine, and climaxes with his leading the French army to liberate Italy. I was lucky enough to be present at the restoration’s first, now legendary screening, at the Empire Theater in Leicester Square, back in 1980.

It was the only venue with a screen wide enough to accommodate the 3-screen/3-projector finale, and an auditorium big enough for a 60-strong symphony orchestra. From the start you could tell you were watching something unique. The effect on the audience was no different from what Brownlow remembers when he first ran fragments of the film on his 9.5mm home projector as a teenager. “The camera did things that I didn’t think it could do, and it represented the cinema as I thought it ought to be, but had never seen an example of. It was beautifully, brilliantly staged. It looked like an 18th century newsreel. You couldn’t believe this had been shot in the 20s.”

When the first of many bravura editing sequences unspooled, the audience knew it was in for a rollercoaster. A snowball fight between two “armies” of young cadets, in which the young Napoleon demonstrates his aptitude for future military leadership by successfully charging and occupying the opposing camp, turned into a pyrotechnical workout for the camera as it was hurled, literally, into the action.

It was many years into his quest for lost footage before Brownlow first clapped eyes on this sequence. He was sitting in the archives of the French Cinémathèque, an organization which had already demonstrated its disdain for what it considered the hubristic efforts of an Englishman daring to restore a French classic. Left alone for a few moments with an unlabelled can of film, Brownlow examined the reel within against the light: “I couldn’t believe it! This snowball fight was like “Rosebud” [in Citizen Kane]. It was constantly talked about as a masterpiece of rapid cutting, but was never seen. And I happened to be very interested in rapid cutting. I thought it had been invented by Eisenstein. When [the archivist] Marie Epstein came back in she was quite upset that I had started looking in her absence, but she had a good heart and coaxed the film through the flatbed viewer, and I always regard that experience as one of the greatest moments of my life.

“It was the most astonishing piece of editing I had ever seen, and it was a perfect example of the avant-garde in the mainstream of French cinema. Gance tried to make the audience into active participants. You get punched on the nose, you fall over, and you run away.” (The editing throughout Napoleon is all the more extraordinary for the fact that it was done by hand, without the benefit of a flatbed or movieola; Gance would hold the film up to the light to figure out where to make his cuts).

Later on, during a dormitory pillow fight, Gance not only accelerates the tempo of his editing with cuts that last as little as a few frames, but also divides the screen into multiple segments, all with their own independent fast-cutting images.

This he considered the first use of what he called Polyvision, which in the final section of the film became three screens – pre-dating Cinerama by twenty-five years.

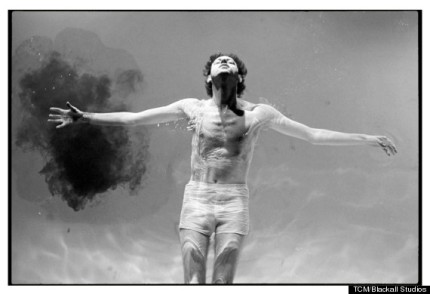

Abel Gance saw film as an immersive medium of poetry and passion, and his editing was as much about conjuring ideas as it was emotions. Brownlow: “In a scene in which Napoleon was escaping from Corsica in a dinghy, he gets caught in a storm and it intercuts with a riot in the Revolutionary Convention. Gance wanted to express Victor Hugo’s thought that to be a member of the Convention was like being a wave on the ocean, and the technical director built a pendulum hanging from the ceiling of the studio, to swing the camera over the extras. I remember Gance saying that the crowd reacted in their cringing very effectively, and you do get the feeling that you’re in the storm at sea, as well as in the storm of the Convention, and you can see a man drowning among his fellow members of the Convention.”

This sequence had a powerful effect on the English director Sir Alan Parker, who was then shooting the big-screen adaptation of Pink Floyd The Wall: “After seeing Napoleon I built a giant pendulum rig over a swimming pool at Pinewood Studios for a scene where Bob Geldof, with flailing arms, seems to be drowning in his own blood.”

Parker continues: “We also threw the camera around at any opportunity, influenced by Gance. A lot of the film was hand-held cameras. Gance taught us that all the usual rules could be broken to create cinematic energy, and a surreal, anarchic, in-your-face film like The Wall was a perfect vehicle.”

Here, from 1980, is a short film in which Kevin Brownlow talks about Gance and his many innovations, with extensive clips from Napoleon:

The great American film director King Vidor once said that music was responsible for half of a film’s emotion and effectiveness. Brownlow is quick to acknowledge that a huge part of the success of his restoration is owed to composer/conductor Carl Davis.

Davis, who was born in New York, is a true polymath, having grown up listening to and performing every kind of music, from jazz to ballet. His move to London in the early 1960s was prompted by the excitement of the arts scene there, and a desire to write music for drama. “There was a lot of classic theater, there was film and the standards of television were very, very high. What went on English TV was very ambitious, and still is.”

Davis met up with Brownlow and his then producing partner David Gill for a TV documentary series about the silent era, Hollywood (1980) which had grown out of Brownlow’s defining book on the subject, The Parade’s Gone By.

Over the course of thirteen one-hour programs Davis had supplied a huge range of music in a multiplicity of styles and orchestrations. In preparation he had spoken to numerous musicians of the silent era, and had integrated their techniques of matching borrowed music with original themes. When it was announced that Napoleon would be their first “live” presentation of a silent, he had just over three months to come up with five hours of music. There simply wasn’t the time for him to compose a completely original score.

Brownlow: “Carl came up with this fantastic idea, an idea of genius, which was to use composers that were alive when Napoleon was alive, which gave the film the most extraordinary authentic feeling, which it has anyway, but it enhances it tremendously.”

At the core of this group of composers was Beethoven, who had famously dedicated his Third Symphony to Napoleon, only to scratch out the dedication upon hearing of Napoleon declaring himself Emperor.

Davis: “Beethoven did four versions of the Eroica theme – the symphony, a set of piano variations, a ballet (The Creatures of Prometheus), and a contredanse. It was an idée fixe for him. I also used Egmont, music for plays, marches, minuets. The idea from an artistic view was not to make it seem random. If the whole film is a biography, a portrait of Napoleon, it could also be a study in the music of Napoleon’s time. Mozart, Haydn, Cherubini, Gluck….“

In typically impish fashion, Gance decided to throw down his own musical challenge. A long, central sequence features Parisians hearing the anthem of the Revolution, the Marseillaise, for the first time, and learning to sing it. This in a silent film! Davis rises to the occasion with a virtuoso set of variations, and elsewhere throws in other popular songs of the period for good measure.

However, one important visual and thematic strand of the film did not yet have a musical identity. Davis: “There was an almost sci-fi view of Napoleon as omniscient, linked to some great force of nature, unstoppable, implacable – an expression of an ideal that had to do with the 1920s as opposed to the 1790s.

“There I had to write something myself that was more like a Hollywood kind of theme – grand, noble, immediately accessible, memorable.”

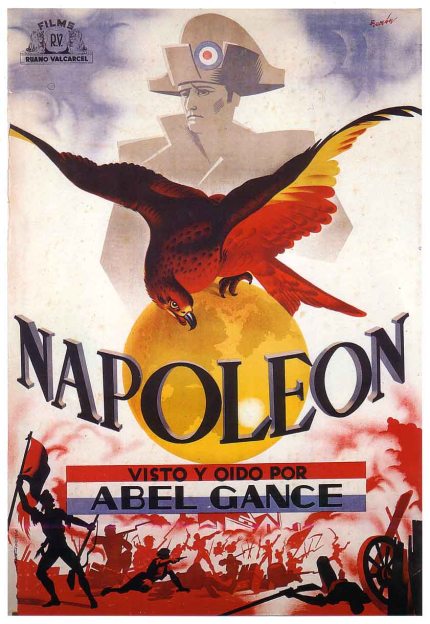

Young Napoleon, taunted by his classmates and disciplined by his teachers, is left alone in a freezing garret. There he is visited by his pet eagle, and in a vivid inspiration, Gance turns the eagle into the visual metaphor for Napoleon’s destiny, to re-appear at key turning points in the film. It is a moment rife with danger, so on-the-nose that it could easily elicit titters rather than awe from the audience. But Davis steps forward with his majestic theme to nail the emotion and the idea behind it. Patrick Stanbury, now Brownlow’s co-producer, but in 1980 just a member of the audience at the first screening, recalls that moment: “Suddenly it was magic.”

Behind the scenes at that first performance in 1980, Davis was heroically keeping the orchestra in sync to the film by his wits alone (disdaining technological assists like click tracks), while the performers were wrestling with some unexpected problems. Davis: “The actual quantity of music that was sitting on the music stands grew and grew, and finally when we got to the third part, which was very long and very stuck together with tape, suddenly all the music fell on the floor. It was in the middle of the Bal des Victimes – very lively using Beethoven’s 7th Symphony. I suddenly lost three quarters of the orchestra, and there is actually a recording of me shouting “Play! Play! Please play!” And we were down on the ground trying to put the music back on the stands again.”

In the following videos, Carl Davis talks at greater length about his score.

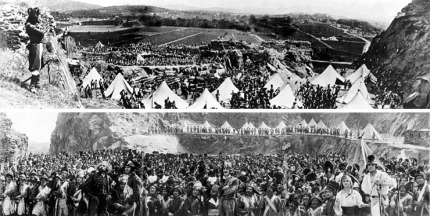

On that faraway day in 1980 at the Empire, Leicester Square, I — like my daughter over thirty years later — would never forget the overwhelming impact of the last act of Napoleon. Suddenly, the curtains at the side of the screen drew back, and the image expanded to fill my field of vision. The audience gasped as one — an effect repeated even more emphatically at the Paramount, thirty two years later. Before us unfurled the spectacle of Napoleon’s army on three conjoined screens, in crystalline black and white. Sometimes the screens join to create continuous panoramas; sometimes they fragment into three sets of evolving images. It’s a spectacle made all the more vivid for its capture by relatively primitive technology. But that does not account for the artist’s eye, of Gance and of his brilliant cinematographers and camera operators. In this triptych sequence the film expands literally and thematically in every direction, juggling static and moving panoramas and montages that gather together all the imagery of the proceeding five hours, hurling it at you with ever increasing density. Those screens are so bright with the projectors’ reflected light it’s as if the theater’s roof has been lifted off and daylight is streaming in on the audience — a cinematic sunrise.

Accompanying this spectacle are the rousing cadences of the music’s climax, a mash-up of Beethoven in full cry with Davis’s own transcendent “Eagle of Destiny” theme.

Back in 1980, when Napoleon finally came to an end (and at a certain point it feels like it will never end — the film just keeps topping itself), the theatre erupted into bravos as the film detonated into the red, white and blue tricolor of its final frames spread across three screens.

For Brownlow, after a lifetime struggling to bring this forgotten masterpiece back into the light, the full force of the experience hit home. In his book he recalls that moment: “I looked at the picture as though I’d never seen it before. I recalled Lillian Gish talking about the premiere of The Birth of a Nation: ‘I sat at the end of a row with men, and during some parts the whole row shook with their sobs, it was so moving.’ Well, I shook my row, and I’m not ashamed to admit it. I was overcome with relief and suffused with joy that the film was at last being seen as it was supposed to be seen.”

For those heading to the Royal Festival Hall at the end of November, that moment can be relived again in all its cinematic glory. Wish I could be there…..

The following “review” of Napoleon includes more excerpts from the film, including the snowball fight (though without Carl Davis’s score, alas).

You can read my full interview with director Sir Alan Parker talking about Kevin Brownlow here. And you can view clips from another classic silent, Flesh and the Devil starring Greta Garbo, with original music by Carl Davis here.

Do you know if there are plans to bring it back to New York. I saw it several times in the 80s at Radio City. I would LOVE to see it again!!!

No plans that I am aware of. Sorry. But glad you saw it in the 80s.

Could you please tell me where you obtained the photo of the 1927 Italian poster? I am writing a book on Napoleon and would like to obtain a HD image of the poster.

Pingback: SILENT MOVIES LIVE AGAIN! | HOLLYWOOD ( and all that )