Tag Archives: Film

HAPPY 130th BIRTHDAY, FRANZ! ( Kafka meets Welles in “The Trial” )

Orson Welles: “What made it possible for me to make the picture is that I’ve had recurring nightmares of guilt all my life: I’m in prison and I don’t know why –- going to be tried and I don’t know why.

“It’s very personal for me. A very personal expression, and it’s not all true that I’m off in some foreign world that has no application to myself; it’s the most autobiographical movie that I’ve ever made, the only one that’s really close to me.

“And just because it doesn’t speak in a Middle Western accent doesn’t mean a damn thing. It’s much closer to my own feelings about everything than any other picture I’ve ever made.”

NARRATOR (at opening of film):

Before the law, there stands a guard.

A man comes from the country, begging admittance to the law.

But the guard cannot admit him.

May he hope to enter at a later time? That is possible, said the guard. The man tries to peer through the entrance.

He’d been taught that the law was to be accessible to every man.

“Do not attempt to enter without my permission”, says the guard. I am very powerful. Yet I am the least of all the guards. From hall to hall, door after door, each guard is more powerful than the last.”

By the guard’s permission, the man sits by the side of the door, and there he waits. For years, he waits.

Everything he has, he gives away in the hope of bribing the guard, who never fails to say to him “I take what you give me only so that you will not feel that you left something undone.”

Keeping his watch during the long years, the man has come to know even the fleas on the guard’s fur collar. Growing childish in old age, he begs the fleas to persuade the guard to change his mind and allow him to enter.

His sight has dimmed, but in the darkness he perceives a radiance streaming immortally from the door of the law.

And now, before he dies, all he’s experienced condenses into one question, a question he’s never asked. He beckons the guard. Says the guard, “You are insatiable! What is it now?” Says the man, “Every man strives to attain the law. How is it then that in all these years, no one else has ever come here, seeking admittance?”

His hearing has failed, so the guard yells into his ear. “Nobody else but you could ever have obtained admittance. No one else could enter this door!

This door was intended only for you! And now, I’m going to close it.”

This tale is told during the story called “The Trial”. It’s been said that the logic of this story is the logic of a dream… a nightmare.

KUBRICK at LACMA

As the stunning Kubrick exhibition prepares to depart Los Angeles, here is a quick tour (with some additional photos). Think of this as a prelude to a future perambulation through the Kubrickian maze….

“Essentially the film is a mythological statement. Its meaning has to be found on a sort of visceral, psychological level, rather than in a specific, literal explanation.” — Stanley Kubrick.

From Kubrick’s photos of New York life in the 1940s in Look magazine:

The art of strategy — the strategist in art. On set and onscreen Kubrick always had a chess game in progress (here in Paths of Glory)

(More photos from Bert Stern’s legendary shoot can be found here).

The alien in the familiar: suspended model of the White Room where Man takes the next step in his evolution (2001: A Space Odyssey)

One possible future of Man —

or another —

Fallout from the film led to Kubrick withdrawing it from circulation in the UK for 27 years. I had to travel to Paris to see it for the first time, dubbed into French

“My candle burns at both ends

It will not last the night;

But oh, my foes, and ah, my friends —

It gives a lovely light.”

What critic Michael Ciment calls “the return of the repressed”, a strand of behaviour that weaves throughout Kubrick’s work, becoming a murderous psychosis signalled by a telltale look:

Private Pyle (Full Metal Jacket):

In flagrante delecto — Masques of the Red Death….

Masks of marriage…..

and celebrity….

“Who’s been sleeping in my bed…..?”

In the room the people come and go….

Talking of Michelangelo….

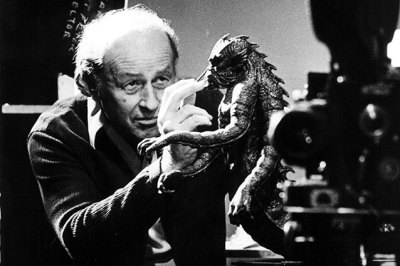

RAY HARRYHAUSEN ( ANIMATING THE IMAGINATION )

Strolling down Hollywood Boulevard a month ago, I found myself swerving to avoid a Spiderman who had temporarily lost control of his web.

Now a native Angeleno will immediately know whereof I speak. I was on the block of Los Angeles that every tourist flocks to, as well as assorted street performers acting out their superhero and celebrity complexes. This is where you’ll find Grauman’s Chinese Theater, home to the concrete signatures, handprints, footprints and even pawprints of Tinsel Town’s legends.

Also along this street you will find the Hollywood Walk of Fame: these are the stars set into the sidewalk of Hollywood Boulevard that bear the names of those who have defined the movies, both in front of and behind the camera. In swerving to avoid Spiderman (who was probably trying to catch the eye of Jimmy Kimmel’s talent spotter), I found myself careening towards a bouquet of flowers set upon an easel above one of these sidewalk memorials. This is what they do here to mark the recent passage of a star from the Hollywood constellation to the Great Walk of Fame in the Sky.

Fortunately, my collision was narrowly averted by a friendly steadying hand from Spongebob (who looked in need of a good rinse). Then I noticed the name of the legend whose floral epitaph I had almost demolished.

Ray Harryhausen.

How appropriate, I thought, as I imagined the headline from the flowers’ point of view: “LARGE CREATURE OF UNKNOWN ORIGIN WREAKS DEVASTATION FROM THE SKY!”. This was exactly the kind of thing you might see in a Ray Harryhausen movie.

Now if you don’t know who Ray Harryhausen is, then you are about to learn about one of the greatest sorcerers of the silver screen. If you are already familiar with his work, and live in Los Angeles, then I suspect you will already be planning to make the pilgrimage to this weekend’s retrospective of his work at the American Cinematheque.

Ray Harryhausen was the master of a process practically as old as film itself: stop motion animation. The ironic thing about those early filmmakers was that after laboring so long and hard to create a technology that could accurately record and then re-project reality, they then almost immediately set their minds to creating fantasies using all manner of camera trickery. Thomas Edison, one of the pioneers of movies, made some of the earliest examples of stop motion animation.

From the beginning, film led a double life. By day, it was a mild-mannered reporter of the factual and everyday; by night, a Jungian fantasist with superhero powers of endless invention.

Stop motion, just one weapon in the technical arsenal of the film wizard, is the process by which an animator films a model one frame at a time, slightly moving the model with each new frame exposure. Then, projected at 24 frames per second, the inanimate model miraculously comes to life. The most famous early examples of this technique used in features were The Lost World (1925) and King Kong (1933). Willis O’Brien, who created the animation for both films, was later Harryhausen’s mentor.

Harryhausen took this technique and expanded upon it, eventually creating his own process to combine models and live action, which he named “Dynamation”.

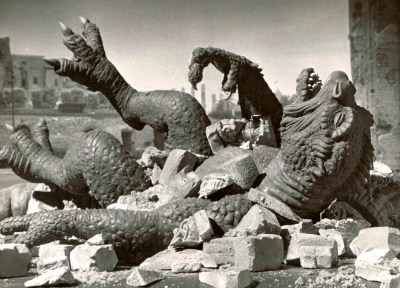

My mind is prone to find odd equivalencies, so I consider Harryhausen to be the Chuck Jones of stop motion model animation. This is not because his films are funny (they aren’t – they are mostly about Armageddon monsters and mythological beasties – but they can give rise to unintentional giggles in rare moments of misjudged invention), but because he brought a level of genius to something that was completely artificial, often visibly so, and imbued it with incredible humanity, rendering it credible and, to the audience, utterly real.

With Jones it was line drawings which, in his greatest cartoons — like the Road Runner meditations on the futility of pursuit, literal or otherwise — were given broad stroke design and crude animation (at least compared to Disney’s fantasias), yet still seemed to capture the deep absurdities and pathos of the human condition. With Harryhausen, when the black-and-white T.Rex from outer space (official name Ymir) in 20 Million Miles to Earth is gunned down by soldiers in the Colisseum, and becomes a ruin in the ruins, guess who we feel sorry for, and guess who seems more human than the humans?

We may be aware of the sometimes jerky movements of Harryhausen’s animated creatures (his preferred term for his creations), the subtle but clear differentiations between the models and the real actors and locations. But at the same time we marvel at the apparent interaction between the models and the separately filmed elements. We buy the fantasy, because we imbue the models with character and emotion. How is that possible? They are just models.

Why do our hearts break at the end of King Kong? How is it that we, like Fay Wray, learn to weep for a rubber monkey?

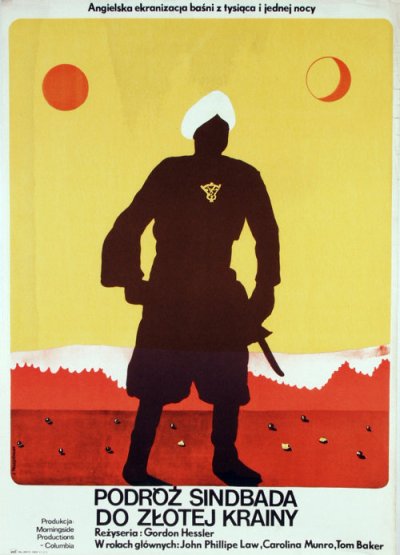

Firty years from now, which version of the Perseus legend are you going to take your kids to see? The recent CGI, 3-D run-amok Clash of the Titans, or Ray Harryhausen’s whimsical 1981 version starring L.A.Law’s hunky Harry Hamlin and his dimple, with Larry Olivier hamming it up as Zeus on Mt. Olympus? (And keep an eye open, or maybe two, for James Bond’s Blonde Venus who arose from the waves: Ursula Andress as — yes, you guessed it — Venus/Aphrodite, minus the conch).

No contest.

So what kind of cinematic alchemy is at work here, decades before CGI is able to render reality with more reality than reality?

Well, maybe that’s the point. Sometimes reality on film is less real, aesthetically and emotionally, than the real thing. Emotional truth is more important than strict pictorial accuracy. Art has always been about the missing piece, the leap of imagination, the interpretative act that is required of the viewer or listener to fully engage with the construct (the art work). In film, as Hitchcock so tellingly observed, it’s what you do not see that tickles the imagination, which in turn teases you into the spaces between the frames, between the visible. This is where the soul of film resides, and where we make the connection with our dream life.

In the pre-digital era the action of creating film was first a physical process, then a chemical one. First the object or actor moves or is manipulated. With Harryhausen his fingers shape and move the model frame by frame, touching it, pouring his energy through his fingers into the rubber or clay. Light bounces off the reality being photographed, passing through lenses onto the recording medium itself, then is manipulated and developed through chemicals in a laboratory, and finally imprinted. It is literally an alchemical process: disembodied light acting on one set of materials to turn them into another. Moving clay or rubber models in front of lights is a physical, organic process: a performance, like that of an actor, except this one is recorded one frame at a time.

On the other hand CGI, the digital equivalent of Harryhausen’s stop motion, takes place in an alternative reality generated within a computer. It is a mathematical process, a sampling of reality dressed up to look like a recording of reality. On some deep, intuitive level, that artificiality is communicated, and our brains, our souls do not completely buy it. We’re used to imperfection in everything we look at and experience in the physical world. Models exist in that world, and carry that DNA with them.

CGI can be further compromised by the desire of the modern filmmaker, paying no heed to Hitchcock, to fill in the blanks: now that he can show everything, he does show everything. There’s no space into which the viewer’s consciousness can quietly slip and settle, then absorb, grow, and make connections.

Harryhausen himself put his finger on it: “There’s a strange quality in stop-motion photography, like in King Kong, that adds to the fantasy. If you make things too real, sometimes you bring it down to the mundane.”

Understanding that music is another magical alchemy that enhances the emotional connection we make to moving images, Harryhausen also made the brilliant decision to hire one of the best composers around, Bernard Herrmann, for four of his films, including his two best: The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and Jason and the Argonauts. It was Herrmann who added soul to Citizen Kane and Hitchcock’s masterpieces Vertigo and Psycho with his bold, imaginative scores. Herrmann was a supreme colorist and a master of inventive orchestration. Harryhausen’s mythic creatures inspired him to create dazzling combinations of unusual instruments to lend each animation its own personality, like the sword-wielding skeleton in 7th Voyage of Sinbad who attacks with xylophone, percussion and brass staccatos.

In the 1970s, Decca’s hi-fi specatacular label, Phase 4 Stereo, embarked on a series of recordings of suites from these scores with Herrmann himself conducting. Their success helped nurture the growing interest in film music as a serious art form in its own right, and are now considered audio classics, with used LPs fetching high prices.

Some years ago I took my then 8-year-old daughter to a screening of The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. She was utterly transported by this Technicolor fantasy voyage come true.

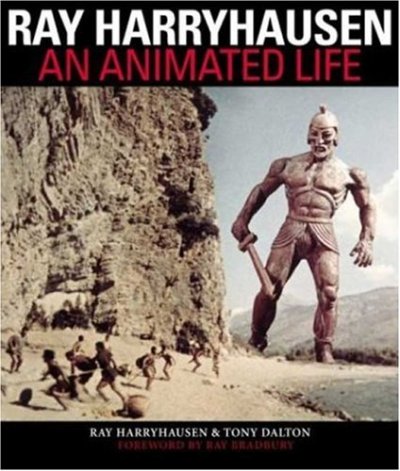

But as far as I was concerned this was just the warm-up to the main event. We walked across the street to meet the man himself, who was signing copies of his latest book.

This was a lavishly assembled collection of stills, drawings and storyboards from his movies, and framed copies of certain drawings hung on the walls of the bookstore. They would not have been out of place in a LACMA exhibit.

Hollywood art. Yes, there is such a thing.

My daughter was excited beyond measure to meet the man whose movie had just brought to life the myths she had only read about in books, or been told by me. Uncharacteristically tongue-tied, she came to the head of the line, clasping the book to be signed.

I told him we had just been to see The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. My daughter was visibly trembling, completely in awe. Harryhausen immediately put her at ease.

“So what did you like the best?” he asked gently.

A pause.

Then: “The skeleton. He – “ note the use of the word ‘he’ rather than ‘it’. Now she hesitated, wanting to be sure to use exactly the right words. “He — was so real.”

“Well”, came Harryhausen’s reply. “He was real.”

Precisely my point.

That book continues to stand in pride of place on my daughter’s bookshelves, next to the Harry Potter novels and other fantasy epics that have so thoroughly colonized the landscapes of her imagination. Mythology and creatures from the beyond will always be with us, as will — thanks to film — the fantastical worlds of Ray Harryhausen.

And I’m willing to bet J.K. Rowling’s a fan too

Sixty years ago, on 2nd June 1953, the BBC mounted its largest broadcast operation to date.

How do you televise a Queen’s Coronation? With great care….