Text originally published in the Financial Times, November 22nd 1986

One of the regular high spots of the London Film Festival in the past half decade has been the presentation each year of one or more silent films with a live orchestra. Sponsored by Thames Television, these performances have not only resurrected the long hidden glories of silent cinema, they have also introduced their audiences to an experience of overwhelming intensity – a far cry from most people’s perception of silent films as dusty, dated entertainments to be watched stoically to the accompaniment off on out-of-tune piano in a cold, almost empty cinema.

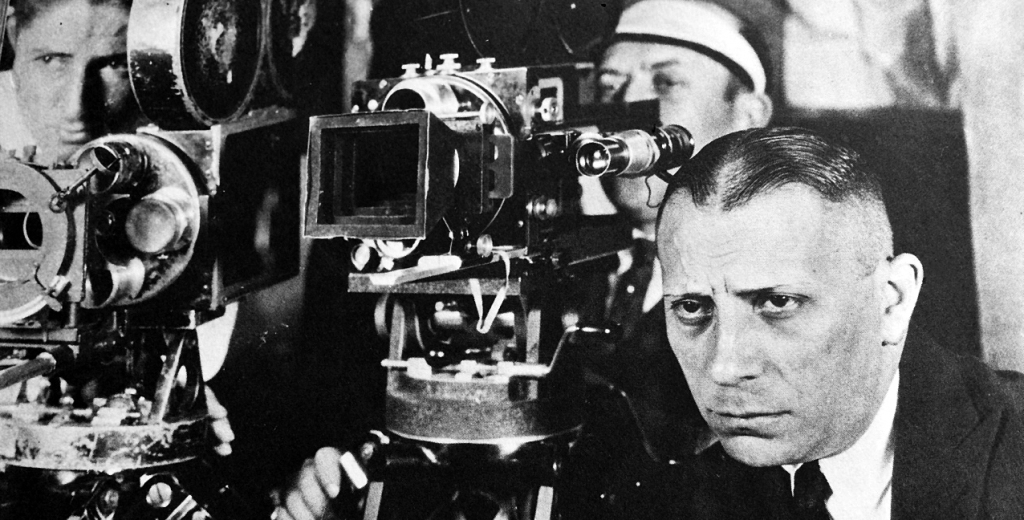

The moving force behind this revival consists of David Gill, a documentary director and producer at Thames; Kevin Brownlow, director and historian of the silent era; and Carl Davis, composer and conductor.

In the late 70s, Kevin Brownlow’s classic book on the early days of Hollywood, The Parade’s Gone By, inspired Jeremy Isaacs, then Director of Programs at Thames, to give the go-ahead for a series about the American pioneers of film. The aim of this series was twofold: to give a history of the early film industry, told largely in interviews with veterans of the period, and to present the actual footage of the time, be it clips, outtakes or newsreel, in as authentic and pristine a manner as was possible.

This involved finding the best possible prints (not always an easy task), projecting them at the correct speed (thus eliminating the traditional “speeded-up” image of silent film), and providing music which would genuinely enhance the visuals. Recognizing Kevin Brownlow’s dedication to the original quality of these old films, David Gill nevertheless had misgivings about how a modern audience would react to them: “I still had a slight reservation because I had been away from silent films for so long. We not only had to demonstrate these films existed and make an interesting, educational program, we had to build an audience, capture their imaginations, make it an entertainment – something they could surrender to. And the only way I could see that happening was not just by using music, but by really spending so much money on the music — composing it and being able to afford a large orchestra, something which documentaries never envisage. Then, as soon as we started seeing the results during the course of production, we were astounded by the effect it had on the film. A whole new entity appeared, and we could see it from the reaction all people who saw the programs.”

Carl Davis had already worked with David Gill on a documentary series, The World at War, and jumped at the chance to score Hollywood. “First of all I did quite a bit of research on how the film scores were created in the period. The series really ran the range of all the styles of film of the period, and involved me in thinking and creating for a great many clips.”

Davis resorted to many of the methods of the silent era: borrowing chunks of the classics, cobbling together popular pieces of the time; anything that would go with the film. Throughout he would interweave his own music, often finding inspiration in certain composers to reflect this style and mood of a film or actor in the accompanying music: Rimsky-Korsakov for Fairbanks and The Thief of Baghdad, Liszt for the soul of Garbo in A Woman of Affairs.

Not surprisingly, Davis was itching to try his hand at a full-length score for full orchestra to accompany a theatrical presentation of a silent film. The opportunity to do so did not arise until the BFI earmarked Kevin Brownlow’s reconstruction of Abel Gance’s epic Napoleon for the London Film Festival in 1980. In three months Davis had to produce five hours of music. As much out of practical as aesthetic considerations he quickly settled upon the idea of using the music of Beethoven and his contemporaries as the backbone for the score, an apt choice in view of the youthful Beethoven’s admiration for the young Napoleon. “One of the first things I learned about silent film musicians of the time, when I was working on the Hollywood series, was that they had absolutely no inhibitions about robbing, like grave robbing, and using classical compositions to support the score.”

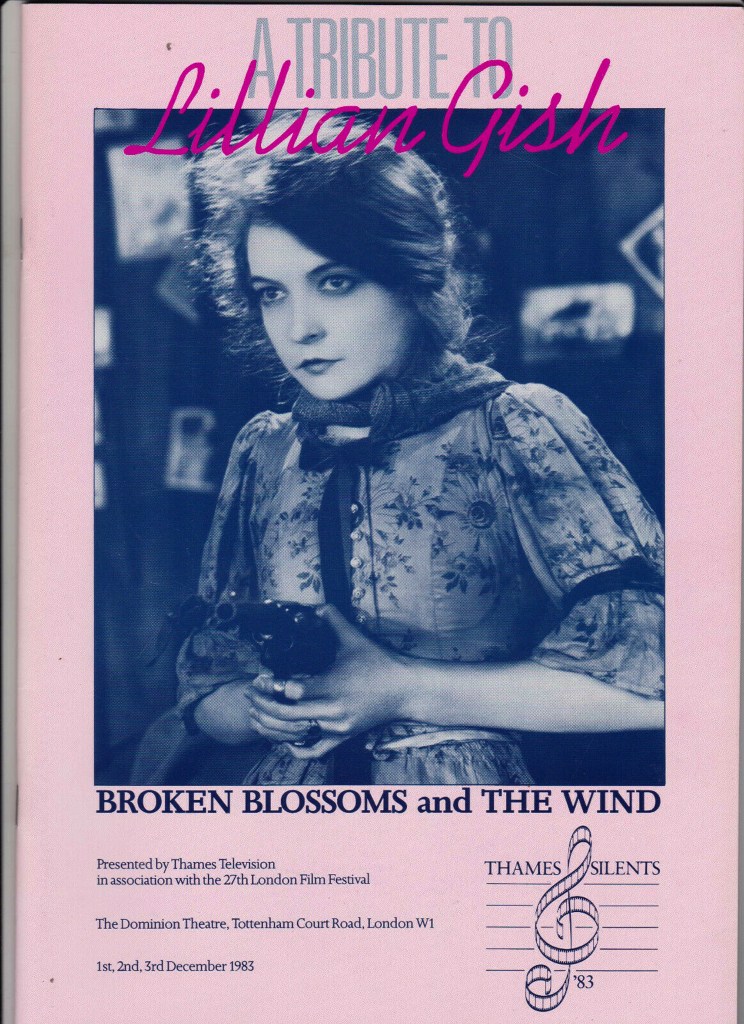

Sometimes an important film would be distributed with a specially composed score. Whenever possible Davis has made reference to these, and has often found useful source material (various army and popular songs of World War I for The Big Parade, for example), and on one occasion has reconstructed an entire original score – for D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms.

But in the case of Napoleon in 1980, Honegger’s original score had yet to be rediscovered, so Davis found himself plundering the treasure houses of Classicism.

Yet he was careful never to use music which might jar with the film’s carefully constructed historical authenticity. “I had a notion, which I always follow, which is to try and be faithful to the period, or at least to pay service to the period it was done in. I would use Beethoven, but only up to compositions off about 1810, and I would not go into Berlioz, for instance, or Schumann or Wagner or any of those pieces which might be appropriate from a mood point of view, but which I felt would betray the spirit all of those wigs, corsets and breeches, so to speak.”

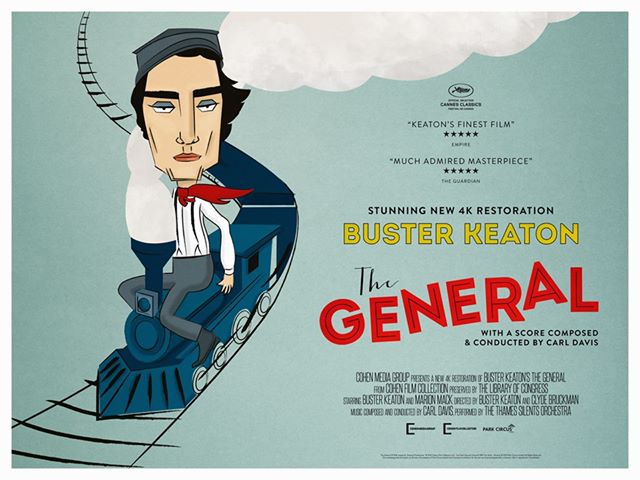

In the films which have followed Napoleon, ranging from romantic melodrama to knockabout comedy, Davis has refined his techniques and approach. Some have been recorded just for broadcast on Channel 4, which aids with the financing. Each film is approached with a fresh musical concept, and careful attention is paid to orchestration to create a distinctive and individual sound world. Structurally Davis relies on a simplified form of leitmotif technique, in which certain themes and characters are represented by easily identifiable melodies that recur throughout the score.

For the broadcast versions of the films, synchronization of picture and sound is achieved in the recording studio through close adherence to a time code printed on the film’s video copy (Davis’s guide when composing). In live performances Davis the conductor has to rely on his internal sense of time and the rhythm, along with his detailed knowledge of the film (described shot by shot in the score), to keep him and the orchestra in the right place.

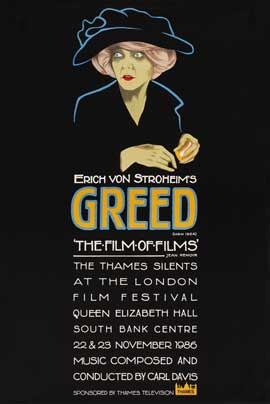

This year’s Thames Silent is Greed, the ”lost” masterpiece of Erich von Stroheim – a grim study of the darker side of human nature.

Davis has drawn his inspiration from Austrian and American music of the 20s. “Though the film is set in San Francisco at the turn of the century, von Stroheim as a director is always very Germanic in his work. The thematic approach, the recurrence of themes, and the fact that the characters come from a German background even — certainly Trina’s Family does – made me lean towards German music, or rather Austrian music, of the early 20th Century. I really didn’t want the orchestra in itself to have a very sympathetic, soft or romantic sound. I wanted it to be harsh and clear – a quality which I think could also describe the way the film is. Alban Berg and von Stroheim would be quite good partners in a way because they are both full of a mixture of banal phrases with a sort of torment: soaring lines and a ‘what-lies-under-the-skin’ kind of character.”

Davis omits strings, except for an elaborate violin solo, leaving wind, brass and extensive percussion. In sequences where several planes of action are involved on screen, he has adopted an Ivesian technique of allowing simultaneous but different music to elide and clash. “For example, during the wedding service a funeral procession passes by. Now if we accept my job as being to bring out what is in the film, it seemed that there was no alternative other than to do a wedding and a funeral going on simultaneously.” Therefore Davis collides Wagner’s Wedding March from Lohengrin in B major with the Chopin Funeral March in B minor, plus a popular song of the period, O Promise Me, in F major.

“This is simply doing what the film is doing, and because of the example of Charles Ives one wasn’t afraid of the clash, one welcomed it. What von Stroheim is actually saying is – this is a wedding that is doomed – and my job then is to reinforce that idea.”

Elsewhere Davis has taken this technique a step further, to bring out what lies beneath the surface of a scene. Two friends quarrel and then make up in a seaside tea shop where a mechanical piano is playing: the steady honky-tonk prattle runs in counterpoint to their reconciliation. The music seems to say: will it last?

Kevin Brownlow comments: “The great director King Vidor says in the Hollywood series that music is 50% of the emotion, and I thought, ‘Come on! This is 30% over the top.’ But he’s right. When you see it working you realize it’s the fusion off the two, like a carbon arc, that creates that fantastic impact.”

Some examples of scenes from Thames Silents productions, all with music by Carl Davis:

Further articles on Kevin Brownlow, Napoleon, Carl Davis, and their revival of silent films with orchestral accompaniment:

Napoleon Redux: The Emperor of Films Returns